This year marks the 700th anniversary of Marco Polo and his adventures in East Asia. Polo’s encounters with merchants, missionaries, and diplomats of diverse backgrounds made his accounts a valuable asset to Europe’s understanding of the Eastern civilizations. Particularly, his exposure to the Mongol courts and ambassadorial service to Kublai Khan has been depicted as more than an East-meets-West tale; Polo helped expand the Mongol Empire’s ties with medieval popes and diplomats. He also helped to maintain that communication so when the time was right, alliances could be made.

Marco Polo, born in Venice in 1254, became a celebrated historical figure who linked Europe to Asia and vice versa. When Polo encountered the Mongol Empire in 1275, its ruler, Kublai Khan, governed modern-day China (where the empire was known as the Yuan Dynasty). By then, the empire had already conquered parts of Eurasia, including Constantinople, the heart of the Byzantine Empire, and parts of what is now modern-day Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan.

The expansion of the empire took it westward into Europe, with the Mongols capturing Kyiv in 1240 by defeating the state of Kievan Rus. As its frontiers expanded, the Mongol Empire continuously searched for military allies from Europe.

In that context, Marco Polo served as a special ambassador for Kublai Khan until 1292. An important emissary, he carried messages between Kublai and several popes and accompanied a Mongol princess to Persia for a royal marriage.

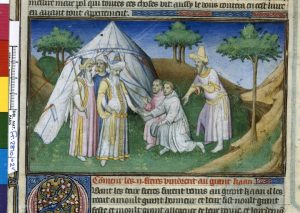

Polo was part of a broader Mongol diplomatic strategy that sought to make use of individuals that had global outreach but also had ties to the pope, the head of Christendom. In the 13th century, other characters such as Guillaume de Rubrouck, and Giovanni da Pian del Carpini also played important roles in connecting the khans to the popes and helping to establish military alliances, which all have contributed to strengthening the Mongol Empire’s diplomacy with Europe in the medieval era. Some of their encounters as diplomatic emissaries were illustrated in medieval artworks by Cardinal Giacomo Gaetani Stefaneschi from 1300-1320.

The Mongol Empire allowed Franciscan missions to expand in Mongol territories, and this augmented Mongol diplomacy with religious entities in Europe. One of the notable diplomatic approaches of the Mongols included having the Franciscan missionaries bring home letters, gifts, and rare goods from the East, which helped maintain communications between European actors protected by the pope.

More broadly, this diplomatic strategy allowed the Mongol Empire to reach beyond its territories. These diplomatic tools would become one of the pillars of Mongol foreign policy.

The start of Mongol diplomacy with Europe can be traced back to the Keraites Mongol tribe’s contact with the Nestorians in the 7th century. The Nestorians were followers of Nestorius, a bishop of Constantinople. The relationship between the early Nestorians and the Mongol Empire was an early example of religious tolerance serving as a cornerstone of Mongol diplomacy, and their relations have paved the way for the Mongol courts to further ties with rest of the Christendom. These early engagements later become more fruitful when the Mongols established ties to Britain, France, and the popes.

Following the first Nestorian encounter with Keraites, the Franciscan missionaries and friars began to play an increasing role in diplomatic matters. Based on the written records of a Flemish Franciscan missionary, Guillaume de Rubrouck, also known as William of Rubruck, the Nestorians were very much influenced by Mongke Khan’s mother, Sorghaghtani Beki (Mongke Khan ruled the Mongol Empire from 1251-1259).

According to Lauren Arnold, an art historian who has conducted life-long research on the Franciscan missions to the East, Rubrouck wrote about his encounter with the Mongol khan:

The Khan had our books brought to him, the Bible and the breviary, and he asked with much curiosity what meaning of the images he had. The Nestorians answered whatever they wanted to, for our interpreter did not come with us… I also had the Bible and he asked to see and examined it a long while. Then he left, but the queen remained, and distributed presents to all the Christians there.”

Rubrouck’s records shed light on the extent of religious actors and their activities at the Mongol courts. He wrote that an Italian envoy, Giovanni da Pian del Carpini, a Catholic archbishop became the first European to enter the Mongol Court. Carpini’s “Ystoria mongalorum” of 1255 would become one of the most valuable European records of the Mongol Empire.

The Franciscans ultimately built the first church in Beijing in 1299, four years after Kublai Khan’s death, during the reign of his successor Temür Khan.

As evidenced in many archival documents in Europe, including France, Italy, and Britain, Mongol diplomacy in the 13th century made strategic use of religious tolerance. These missionaries and their servitude to the khan strengthened Mongol diplomacy with Europe. Many of their names have been lost to history; another such emissary in the 13th century – Rabban Bar Sawma, a Uyghur monk – was only rediscovered through records in the Archives Nationale in Paris in the 18th century.

These rare archival documents reveal the ways in which the Mongol Empire approached Europe by accepting their religion as part of a greater diplomacy with the whole continent.

The Mongols sought to utilize religious diplomacy with Europe was to establish military alliances. The first major Mongol-Europe military alliance came about by connecting with the kings of France and England. The alliance would defeat Muslim territories in the Mongol quest to conquer the Middle East.

Historians of the medieval era argue that the Mongol Empire sought to use its links to Christianity to further military diplomacy with Europe. As Arnold wrote:

Several Khans – particularly the rulers of the Il-Khanate, which occupies current day Iran and Iraq and bordered the Muslim-held portions of the Holy Land – held out the lure of their own baptism to keep the West interested in the exchange.

In strengthening the Mongol Empire’s ties to Europe, it behooved the khans to establish a relationship with the head of Christendom: the pope himself.

The popes of Europe had a decisive role in Europe’s relationship with the Mongol Empire. Timothy May, a leading Mongolian Studies scholar, wrote that the Pope Alexander IV “vigorously instructed King Bela IV [of Hungary] (r. 1235–1270) to decline an offer of a marriage alliance with the Jochid Mongols in the Pontic steppes, better known as the Golden Horde.”

One of the main reasons for Alexander’s refusal was that the Mongols were not Christian and not baptized. But the pope was also right in a strategic sense: an alliance with the Mongols might pave the way for them to invade Hungary. Eventually, the Mongols did just that in 1241.

The papal relationship with the Mongols improved over time, however. Pope Gregory X, from Italy, had a strong interest in converting the Mongols, which fostered close exchanges. The Vatican Apostolic Archive inventory documents items of Mongol origin that were “already in the treasury of the pope by 1295.”

In 1274, the Second Council of Lyon convened and discussed the importance of a “truly unified front in attacking the Muslim threat in the Holy Land. The call for Crusade of all Christians was agreed by major European powers at that time, England, France, Aragon, and Sicily.” The Mongol delegation too attended the council’s meeting, seeking a military alliance.

The Mongol Empire’s relationship with the popes reached a peak in the latter 13th century. These remarkable relationships helped Mongol diplomacy to set foot in Europe, expanding exchanges and diplomatic ties. Remarkably, the relationship has been maintained into the next millennia: Pope Francis’ state visit to Mongolia in 2024 once again augmented Mongolian diplomacy with Europe and rest of the Christendom. But more importantly, it showed that, just like under the khans, religious tolerance remains an important pillar of diplomacy that help Ulaanbaatar navigate global challenges.