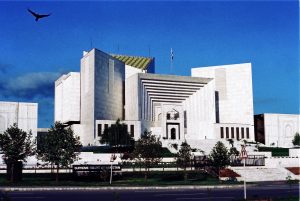

In a development likely to have far-reaching implications for Pakistan’s judicial landscape, the Supreme Court has appointed Justice Amin-ud-Din Khan as the head of its first-ever constitutional bench. The move comes in the wake of the recent passage of the 26th constitutional amendment, which has redefined the powers and roles of the judges of the apex court within the country’s legal framework.

It is widely believed that Khan is a judge who follows the law and does not take sides in political disputes. He recently headed the larger bench hearing the government’s intra-court appeals against the ruling that declared civilian trials in military courts unconstitutional. Unlike many other judges in the past, he may not challenge the government or Parliament’s decisions as the head of the constitutional court. This may not sit well with the opposition parties, who want the judiciary to play an active role in settling disputes concerning controversial laws passed by Parliament.

The constitutional bench was established under the 26th amendment, which empowers legislators to have greater influence in appointing top judges while simultaneously restricting Supreme Court judges from hearing cases pertaining to constitutional issues. Instead, as per government officials, these matters will now be addressed by a select panel within the Supreme Court, thereby streamlining how such disputes are handled.

Notably, this amendment coincided with another critical reform that extended service tenures for top military chiefs from three to five years, and set a fixed term of three years for the chief justice of Pakistan regardless of age considerations.

According to government officials, the recent constitutional changes, which extend military leadership tenure and limit judges perceived to be undermining governance, represent a pivotal step toward stabilizing the country’s political system.

If viewed solely through the lens of calming Pakistan’s tumultuous political environment with a view to facilitating the execution of financial reforms, the passage of these legislations may be essential for the current government, which relies heavily on the military leadership not only for its survival but also to implement stringent economic measures stipulated in the ongoing International Monetary Fund deal.

Pakistan’s economy is currently facing significant challenges, struggling to regain stability while reform measures announced in recent years encounter substantial resistance from various sectors, including the bureaucracy itself.

The institutions targeted for reform are so beleaguered that they deter private investment. A prime example is Pakistan International Airlines (PIA), which has been at the forefront of reform initiatives. Despite over two years of efforts to privatize PIA and attract private stakeholders, recent bidding processes have failed to draw any credible buyers. This alarming trend underscores that even with a supportive ruling structure, revitalizing loss-making institutions remains an uphill battle.

For meaningful progress in these reform projects, continuity and consensus among the military leadership, civilian government officials, and judicial support are imperative, a government official told The Diplomat on condition of anonymity. “Stability in governance is crucial for Pakistan to fulfill its economic agenda without fear that a sudden change in leadership could jeopardize both current operations and future plans for reforms,” the official said.

The ongoing political turmoil between the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz-Pakistan People’s Party coalition on the one hand and the opposition Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) further complicates the situation. The ruling alliance perceives PTI chief and former Prime Minister Imran Khan as a significant threat not only to their economic reform initiatives but also to their grip on power. Even from prison — where he faces multiple corruption charges — Khan continues to challenge the current regime’s ability to implement reforms through protests and questioning the legitimacy of the current ruling alliance.

It is likely that Pakistan’s key allies, China and Saudi Arabia, will not be against the idea of a stable civil-military regime that stays in power for a longer period, as that would provide continuity in policy as well as relative stability in relations with Islamabad.

This approach could potentially facilitate policy continuity in Pakistan, as these nations have become accustomed to negotiating with various premiers and officials. However, the political landscape in Pakistan is notoriously fluid. Thus, it is common for one official to be replaced by another in a relatively short timeframe.

That said, the ongoing efforts in Pakistan to extend the tenures of top government officials while sidelining others raise critical questions about governance. It remains uncertain whether these moves will foster the continuity and space required for credible governance. Critics argue that recent constitutional amendments aimed at extending tenures are politically motivated strategies designed to undermine rivals rather than genuine attempts at reform.

Moreover, the manner in which these amendments were passed through Parliament has been met with skepticism. In a country where transparency is often lacking — whether concerning reforms or elections — such actions can deter potential investors who might otherwise consider contributing to Pakistan’s future.

Whether these constitutional changes are truly beneficial for Pakistan or will simply serve as tools for political maneuvering amidst an ever-shifting landscape remains to be seen.