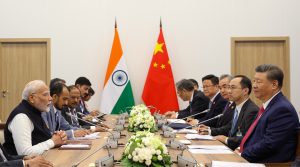

In late October, India and China finalized a deal to pull back troops from two key Himalayan flashpoints in eastern Ladakh. This was a welcome reprieve after over 20 rounds of often lackluster, grim-appearing negotiations and no letup in Chinese transgressions (for example, in Tawang and Barahoti). Soon after the agreement was reached, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping met at the BRICS summit in Kazan, Russia, and signaled their evolving political intent for “peace and stability” after maintaining a cold shoulder for almost half a decade. A formal dialogue had eluded them since the much-hyped but ultimately deceptive meeting in Mamallapuram in October 2019.

These signs of an apparent thaw have sent political commentators into a tizzy. The new announcement appeared jarring to some, mainly because a month earlier, in September, Modi was hobnobbing with the outgoing U.S. President Joe Biden in his hometown of Wilmington, Delaware for the all-important Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad comprising Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S.) leaders’ summit – a mainstay for the four members and other stakeholders’ Indo-Pacific visions and strategies.

For China, the Quad is a true embodiment of the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific construct. Beijing’s perception of the grouping has evolved from dismissing it as easily dissipated “sea foam” to seeing the Quad as an “anti-China” bloc fostering regional divisiveness.

India’s precarious China-U.S. balancing act will get a fresh twist in the coming months with U.S. President-elect Donald Trump, who, in his first term as president, famously got along with strongman Modi, reportedly having picked well-known “China hawks” for top diplomatic roles in his incoming administration.

India’s diplomatic prescience, or at least deftness, becomes all the more vital when viewed through the prism of global leaders (from Europe to East Asia) who have proclaimed the accelerating trends toward multipolarity – a multipolar Asia and world ranks high among India’s foreign policy priorities, too.

So does the China-India thaw, along with India’s redoubled participation in China-dominant non-Western forums like the newly expanded BRICS summit, indicate India’s intention to reduce its tilt to the West, particularly the United States? And more importantly, what does this mean for India and its Indo-Pacific priorities?

India’s priorities for the Indo-Pacific order align with its outlook that a multipolar Asia is the best paradigm for peace and stability. In that vision, an economically developed and strong India is critical. It is precisely this dual track of a multipolar Indo-Pacific and a strong India that the country pursues across virtually all wind directions and strategic sectors.

In the Tussle for Multi/Bipolarity, the Indo-Pacific Remains the Focus

In the growing bipolar dynamics between the United States and China amid the high stakes high-tech rivalry, India’s attempts toward a “multi-aligned” strategic rebalancing are gaining ground. Even though China is still India’s top trading partner, the former is a continuing perceived threat along the Himalayan border and in the maritime domain, particularly in the Indian Ocean region (IOR), the recent thaw notwithstanding.

As a result, as part of its objective to strengthen itself, India has solidified its technological, defense, and security ties with China’s primary rival, the United States. Be it launching the Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET) and the India-U.S. Defense Acceleration Ecosystem (INDUS-X), expanding bilateral and multilateral maritime exercises, building a joint semiconductor fabrication plant, conducting collaborative research in the outer space sector, creating critical minerals supply chains, or cooperating on emerging digital technologies in Asia and Africa, the U.S. has in the Biden years perhaps become India’s most valuable partnership. Indeed, as a coercive actor in the region and a (perceived) threat to India, China has been a central aspect of this partnership.

At the same time, India has diversified its engagements by strengthening economic and trade, diplomatic, digital (including critical technologies such as semiconductors), and maritime security cooperation with various countries. Mainly, India has actively pursued ties with “like-minded” Indo-Pacific stakeholders. India has tightened cooperation with partners like Australia, the European Union, European major powers like France, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, and the U.K.; Japan, the Philippines, South Korea (though ties have not fulfilled their potential despite much ado), and Vietnam. India has also reached out to technological superpower Taiwan, although that marks a redline with China, and so the budding strategic outreach would be tricky. This pursuit of varied partners – all efforts to promote multipolarity – is as much to counter the bipolar compulsions due to the China-U.S. rivalry as to counter China’s growing footprint in India’s backyard of South Asia and the IOR.

Europe Is a Flourishing and Fast-Growing Pivot

In that vein, India’s still-evolving outreach to various parts of Europe, including the EU and its members, and recent concerted wooing of Southeast Asian states like Singapore and the relevant regional multilateral organizations are particularly noteworthy among India’s outreach activities. As China’s growing coercion against states, including in Europe and Asia, has intensified, European partners, particularly the EU, have looked to strengthen their Indo-Pacific strategies. India has seized the moment to become Europe’s top priority.

India has boosted its links to all parts of Europe through high-level engagements, including Modi’s visits to Italy, Poland, Greece, Ukraine, Austria, and Denmark (for the Nordic summit), to name a few in the last couple of years. Notably, India’s diplomacy is not limited just to the traditional partnerships, say with France or Germany – although the latter have not lost space in India’s diplomacy, as is evident from German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s recent India visit, for example.

The results have been mixed. The launch of the Trade and Technology Council (TTC) has been historic, and enhanced coordination, including new collaborations (for example, on recycling e-vehicle batteries), has come up. New high-tech-oriented economic ties, including on semiconductors, with the EU will also enable India to give impetus to its economic superpower potential. Moreover, India has been able to push for connectivity initiatives via the EU’s Global Gateway, including the collaboration with the European Investment Bank (EIB).

Yet, as the ongoing negotiations for the India-EU free trade agreement (FTA) suggest, more must be done to mitigate fundamental differences and boost political will. Notably, India needs to work with the EU, a reliable bloc with high-tech capabilities, on climate action and innovation and regional economic integration in India’s immediate neighborhood and Southeast Asia, where China has tremendous clout. This will benefit the partners economically and strengthen the Indo-Pacific order without resorting to obvious moralizing.

But the Core Lies in Modi’s Southeast Asia Pitch

Since his first term of “Acting East,” Modi has been vocally ambitious about Southeast Asia, even if linkages may not have lived up to his vision yet. Modi sought to primarily draw on the historical and cultural linkages between South Asia (south India) and Southeast Asia. The two regions, however, famously lack integration despite booming potential – as per a 2022 World Bank report, trade linkages between the two subregions grew about nine-fold over the past two decades, from $38 billion in 2000 to $349 billion in 2018. As a dialogue partner and comprehensive strategic partner of the the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as well as an East Asia Summit (EAS) member, India has been constantly championing ASEAN centrality in its Indo-Pacific outlook on order. Yet the potential has not been fully tapped.

Nonetheless, Modi’s recent visits to Singapore and Brunei highlighted good tidings regarding future-oriented diplomatic, economic, and strategic ties between India and ASEAN states in the Indo-Pacific. In Brunei, India upgraded ties, deepening cooperation in defense, trade, investment, technology, renewables, climate change, and regional security avenues. In Singapore, the so-called gateway to Southeast Asia, India showcased that its ambition to build itself as a manufacturing hub in the new digital era would necessitate strategically incorporating Southeast Asian states into the mix, as evidenced by the India-Singapore Semiconductor Ecosystem Partnership.

Moreover, Vietnam and the Philippines’ upswing in defense cooperation with India, including arms sales, indicates that bonding over the perceived threat from China as a common factor will impact their ties going forward. India’s tacit support of the Philippines and evolution in its South China Sea stance highlight the regional “convergence of interests,” particularly India’s growing stress on the maritime domain of the Indo-Pacific.

Building Tricky Bridges?

Notably, Modi, in recent times, has also shown a penchant for embracing contrasting worldviews. He has courted Russian President Vladimir Putin and extended a historic outreach to Ukraine by visiting the two warring states back to back. The former move expectedly drew criticism in Kyiv and the West, but the overall strategy has, to an extent, worked for India. It is important to note that amid the geopolitical contest between Russia and the West, India has not isolated Russia as a vital partner. At the same time, India’s relationship with Russia is not a strategic priority, “with the primary focus instead being strategic maintenance rather than elevating relations.”

In West Asia, too, although commentators have called out India for tacitly backing Israel under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Modi has equally reached out to the Palestinian leadership. Undoubtedly, India’s engagement with Israel has, in the last decade, become well-rounded (from defense to innovation), without New Delhi shying away from showcasing its interests beyond the ideological. Yet, the political tightrope has not been discarded: there is continued emphasis on a “two-state solution,” ceasefire, and a return to diplomacy and dialogue.

Moreover, India’s ties with the other states of West Asia are historically high, from the cross-sectoral comprehensive strategic partnership with the UAE to India and Iran signing a 10-year deal on Chabahar despite India’s potential risk of embroiling in U.S. sanctions. With China having expanded its strategic footprint in West Asia (exemplified by the brokering of the Iran-Saudi Arabia deal), India has displayed more foresight in multipolarizing this region.

India’s Strategy Makes Sense

Keeping Trump’s last term and his “transactional diplomacy” in mind, it is apparent that the push for multilateralism seen in Biden’s term (“restoring American engagement internationally”) will give way to enhanced focus on bilateralism and minilateralism – championing the values of the so-called “multilateralism à la carte.” Even as India has been a fervent proponent of effective multilateralism via reforms in multilateral institutions, a minilateral approach suits India just fine.

For example, India has effectively utilized the Quad – rejuvenated under Trump 1.0 – to expand its global profile and provide momentum for developing a credible security mechanism in the Indo-Pacific. Flexible arrangements like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), which is not an FTA, have also allowed India to push for interests-based goals such as strengthening supply chains, while opting out of the IPEF’s trade pillar.

At the same time, India’s proactive participation in U.S.-led initiatives like Quad and non-Western forums like BRICS – the latter are expanding amid a void of functioning multilateralism – ultimately highlights its broadened appeal.

Against that overall scenario, a question also arises: whether India will be willing to leverage its new apparent softening toward China – another strong Global South leader with a broader appeal – as part of India’s deft balancing act between the West/North and the East/South. It is clear that the China-India hostilities are unlikely to cease, nor is India’s aversion to Xi’s controversial mega-project of the Belt and Road Initiative going to change.

Nonetheless, that the two regional rivals have already cooperated as founding members of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), among other fora, highlights the unpredictability and flexibility of global transactional politics. Trump’s reemergence will only strengthen such maneuvers. By and large, India’s approaches to fostering the Indo-Pacific order align with its outlook that a multipolar Indo-Pacific that includes a strong India is the bedrock for peace and stability. In that vein, India’s modus operandi blends realpolitik and flexible diplomacy – and who could fault that?

This work is part of a Stiftung Mercator-funded project titled “Order in the Indo-Pacific: Gauging the Region’s Perspectives on EU Strategies and Constructive Involvement.” The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of Stiftung Mercator or the authors’ respective institutes.