M’s situation is increasingly stressful, as his asylum claim is teetering on the edge of deportation back to Greece. He arrived in Germany three years ago after months on the island of Lesvos, Greece where many Afghan refugees arrive in Europe.

Identified as M for the sake of anonymity, he exemplifies the fear faced by many Afghans amid high uncertainty around Germany’s ever-tightening migration policy. “The prospect of being sent to Afghanistan is so terrifying that I would rather be dead than go back there,” M says.

The court’s initial decision in December was not in his favor, and he’s acutely aware that judges tend to rule against individuals coming from Greece or Italy. His expired identification documents further complicate his situation. M fears that deportation to Greece could lead to imprisonment and eventual deportation back to Turkiye or even to Afghanistan, a country he has never known.

Like many hundreds of thousands of Afghans who have sought refuge in Germany, M’s journey has been long and arduous, fraught with danger and setbacks every step of the way.

Many Afghans have lost their lives attempting to cross Lake Van in overcrowded boats organized by smugglers after navigating the Zagros mountains from Iran. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

As an Afghan whose parents fled the Taliban, he grew up in Iran, constantly facing discrimination, violence, and perpetual displacement without proper documents. His journey to Europe was perilous: crossing through Iran and Turkiye to Greece. The trek involved crossing the Zagros mountains between Turkiye and Iran, where scores of Afghan refugees have risked their lives trying to avoid being shot by Iranian and Turkish border guards; weathering the treacherous and gigantic Lake Van in a rickety boat to avoid police detection; and then traversing the whole of Turkiye to eventually board a small rubber dinghy in the middle of the night to cross the narrow stretch of sea to Lesvos, Greece.

Recent changes in German migration policies have intensified M’s fears. There’s a growing itch in Germany to further tighten the borders and deport asylum seekers, particularly Syrians and Afghans. Most worrying are the significant political gains in several states made by the far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD), which has risen to prominence around its anti-immigration rhetoric. To compete with the growing influence of the AfD, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and Christian Democratic Union (CDU) have followed suit by adopting their own tougher stances on migration.

A view from Assos, Turkiye, of Lesvos, a Greek island that has become a crucial crossing point for Afghan refugees attempting to reach Europe by boat in recent years. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

A Deluge of Changes

According to RFE/RL’s Radio Azadi, there were 39 deportation flights from Germany to Afghanistan between December 2016 and June 2021. Young Afghan men were especially affected if their asylum cases had been rejected. When the Taliban took over in August 2021, Berlin ceased deportations to Afghanistan, considering it unsafe.

The situation changed again this June when German Chancellor Olaf Scholz vowed to resume deportations of criminals from Afghanistan and Syria after a deadly knife attack on a police officer by an Afghan refugee.

After a second knife attack in Solingen in late August by a Syrian man, calls grew even louder for the German government to act. CDU Chairperson Friedrich Merz called for a “halt to the admission of asylum seekers from countries such as Syria and Afghanistan and implementing consistent deportations there. In addition, anyone who travels from Germany to their home country as a refugee must immediately lose all protected status in Germany.”

Later that month, some politicians in Germany called for Afghans and Syrians to be refused entry to Germany altogether. Interior Minister Nancy Faeser pledged to “make deportations easier.”

In August, a deportation flight, brokered by Qatar, carried 28 men to Kabul.

“We did see a first deportation flight, which was actually the first flight to Afghanistan from the EU as a whole since the Taliban took over, at the end of August this year, which was also not so coincidentally two days before the elections in Saxony and Thuringia,” says Weibke Judith, the legal policy spokesperson at the prominent German refugee organization Pro Asyl. The far right AFD party won the largest vote share in both of those states.

Merz is the front-runner to become the next German chancellor in elections scheduled for February and has vowed to dramatically change course on the previous government’s migration policy. Scholz lost a vote of no confidence in mid-December. The Merz-lead CDU party is calling for a markedly tougher position on immigration and asylum, and an increase in expedited deportations to “safe” countries.

Judith sees a worrying shift in asylum decisions, suggesting a possible return to stricter policies in the near future for certain groups of Afghan asylum seekers in Germany.

“Since the summer this year, we have started to see more and more rejections again, especially for young men… claiming that for kind of like young, fit men, if they have a family network in Afghanistan, that it’s safe to return if they cannot prove that they had specific troubles with the Taliban in the past,” she says.

An immigration detention and removal center in Van, Turkiye, which has held migrants mainly from Afghanistan and has received EU funding. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

By mid September, policies had already become even more stringent. The announcement of border checks at all German land borders were implemented to “limit irregular migration further” and to “protect Germany’s internal security” with a “need to protect against Islamist extremist terrorism and serious cross-border crime.” Many experts viewed this move clamping down on migration as primarily targeted at specifically deterring Afghans and Syrians.

Furthermore, Germany announced plans to stop providing financial support to asylum seekers who fall under another EU country’s responsibility, according to the Dublin Regulation in 2025, and promised to ramp up efforts to increase the number of individuals returned to the EU country they first entered.

The heavily militarized border wall between Turkiye and Iran poses significant challenges for Afghans crossing the Zagros mountains, as they must find rare openings to evade detection amid increased security measures funded by substantial EU border investments over the past decade. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

“The number of those [migrants] who come to Germany irregularly is too large. And it is therefore in the understandable interest of the German government to ensure that we get these things under control through good management of irregular migration,” said Scholz.

Scholz made these comments on Germany’s implementation of land border checks during a visit to Uzbekistan. Reporting suggests that Berlin has been quietly negotiating with Uzbekistan and other countries neighboring Afghanistan to receive Afghans deported from Europe.

Judith is worried that more deportation flights could happen in the near future.

“We are worried that the pressure will grow to have semi-regular flights from Germany to Kabul. We also expect that if this happens, it will concern not just people who have committed some criminal offense.”

Theresa Bergmann, an expert on Asia from Amnesty International in Germany, is also concerned about the prospect of any type of deportations, which Amnesty views as unlawful.

“Due to the arbitrariness and complete unpredictability of Taliban rule, all deportations to Afghanistan are illegal. Any person returning may face torture; therefore deportations constitute a violation of the principle of non-refoulement under international law. Due to the universality of this principle and of human rights in general, this applies to all population groups without exception – including alleged criminal offenders,” she says.

Nor does she see any improvement in the security environment since the Taliban regained power.

“Amnesty International has extensively documented how the human rights situation in Afghanistan has steadily deteriorated since the Taliban takeover in August 2021. We documented how the Taliban have continued to increase brutality, including through the reintroduction of physical punishments such as flogging and stoning. Due to the horrendous human rights situation, Afghanistan cannot be deemed safe – for anyone,” says Bergmann.

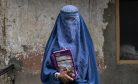

A significant relief came for Afghan female asylum seekers this October when the European Court of Justice ruled that Afghan women face systematic persecution under the Taliban regime, making them eligible for refugee status in the EU based solely on their gender and nationality and guaranteeing them protection from deportation.

Concerns Over Diplomatic Relations With the Taliban

Judith also has strong concerns about the implications of German deportations in potentially legitimizing the Taliban’s rule.

“Either way, in our opinion, it is kind of starting the path to normalization of the Taliban regime. And that is just something that we fundamentally disagree with, and that we think is quite a dangerous slope to normalize a regime which has established some of the worst atrocities towards women, but also that affects anyone living in Afghanistan,” she says.

Despite these policy shifts, Berlin has insisted it maintains its stance against normalizing relations with the Taliban and has said there will be no efforts as long as “current conditions persist.”

Afghanistan expert Thomas Ruttig told DW that the Taliban regime is “selling the fact that Germany is conducting technical discussions as an important step toward diplomatic recognition.” He added that “the German side will attempt to downplay such claims, but of course in light of current talks about deportations to Afghanistan, they are interested in them.”

The fears of Afghans living in exile about Germany’s increasing relations with the Taliban are not completely unfounded. The New York Times’ Christina Goldbaum wrote in October that “more European leaders and international organizations have appeared to accept the limits of their influence and engage on issues where they can find common ground.”

Goldbaum reported, “Leaders of European countries are motivated to engage with the Taliban by two fears: that waves of Afghan migrants will enter Europe if there is turmoil in Afghanistan, and that terrorism could emanate from Afghanistan and reach Europe.”

Officially, Germany does not have diplomatic relations with the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. But this July, the Taliban started to apply pressure on Afghan diplomatic missions in Europe, Germany included, informing their host countries that documents issued by these missions would no longer be recognized by the Taliban and invalid for use in Afghanistan.

To the dismay of the Afghan diplomats in exile who had been working since before the Republic’s collapse, the embassy in Berlin and the consulate general in Bonn were explicitly mentioned. The Taliban wanted to put an end to the Berlin embassy’s ability to issue official documents.

During this three-year period, the Afghan diplomats in Berlin and Bonn had been issuing passports and other documents to the sizable diaspora of Afghans in Germany. There are currently 400,000-500,000 in exile.

The Afghan embassy in Berlin has operated independently and does not adhere to directives from the Taliban, serving as a critical lifeline for Afghans seeking assistance abroad. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

The Taliban’s withdrawing their recognition of the Berlin and Bonn missions has now put those missions on the verge of closing and irrelevance.

By September, DW reported that it was in possession of a copy of the document confirming that the German Foreign Ministry had accepted the fact that Afghanistan’s mission in Munich had taken over all consular responsibility for Afghans in Germany.

Soon after, Afghan embassies in Europe (including in Norway and in the U.K.) closed.

The Afghan consulate in Munich, which is confirmed to be under the direction of the Taliban, is now making significant amounts of revenue from the consular services it took over from Berlin and Bonn. It is forcing Afghans to interact with the Taliban-connected authorities who work there. There is a major concern among Afghans in Germany that their personal data will be accessible to the Taliban and that it would likely put them and their family members still in Afghanistan at major risk.

This had happened in similar fashion inside Afghanistan in 2022, according to a Human Rights Watch investigation. HRW detailed how the Taliban control systems hold sensitive biometric data that Western donor governments left behind in Afghanistan in August 2021. That is “putting thousands of Afghans at risk,” HRW said.

An abandoned backpack lies near an underpass in Tatvan, Turkiye, a stark reminder of the many Afghans who sought shelter here on their perilous journey westward after crossing into Turkiye and navigating Lake Van. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

In November, Ruttig wrote in the German outlet Taz that the German government had forced the ambassador in Berlin to resign. In response to a request from Taz, “the Federal Foreign Office stated that the Federal Government had not made any changes to the status of the Afghan diplomatic missions in Germany. The two heads of the Afghan diplomatic missions in Berlin and Bonn were recalled by the sending state.”

Ruttig views these actions by the German government as “in blatant contradiction to its official Afghanistan policy.” He theorized that “the background to the German action is probably the deportations to Afghanistan pushed forward by Chancellor Olaf Scholz.”

In a provocative action last month viewed as an emboldened step by the Taliban, Abdul Bari Omar, a Taliban official, visited a mosque in Cologne and ignited a major controversy. Germany said Omar did not have permission to visit.

The German Foreign Ministry repeated its position that there would be no normalization with Taliban authorities if they “continue to exclude half of the Afghan population from participating in society and blatantly trample on human rights, especially women and girls.”

Experts on the region are skeptical.

“Germany saying that it has no ties to the Taliban is a bit ridiculous. The EU maintains a diplomatic mission in Kabul (the only Western diplomatic mission apart from the U.N.) and talks to the Taliban all the time. I don’t know why they needed to loop in Qatar,” says one Afghan expert. The EU held talks with the Taliban in Qatar back in 2021.

In Germany, Slow Integration and Insufficient Support for Arrivals

In the last decade, for the many Afghans who came to Germany, “There were some who got asylum but there were others who were rejected by the federal office for migration and refugees authority. Some sit (in refugee centers) in the old Berlin airports of Tempelhof, others in Tegel. As the German government knows the harsh situations in Afghanistan over the last years, they were not sent back,” says Sascha Langenbach, press officer for the Berlin State Office for Refugee Affairs.

The historic Tempelhof Airport in Berlin has been repurposed to house Afghan refugees in temporary containers for over a decade. Many others now wait in the old Tegel airport, which houses thousands of refugees. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

“Several thousands of Afghans are here and do very well. But we have other examples where people find it extremely hard to make Germany their new home,” he says.

Bureaucratic and high language barriers make things extra challenging.

“With discussions in German politics these days, I can understand that they do not feel very secure if they are not integrated or not feeling that they are integrated or welcome. Well-integrated means language and working experience, but this is very hard. Especially for those who arrived recently after the Taliban regime takeover in Kabul and from other major cities in Afghanistan,” he says.

There are challenges faced by Afghan refugees in Germany due to negative stereotypes and public perception.

“People from Afghanistan are so often now portrayed as, you know, prone to crimes, etc., as being dangerous. I think this is just also something that, of course, impacts people in how other people deal with them,” says Judith.

She says there is a critical need for integration and mental health support for refugees, and she is concerned about recent budget cuts in these areas.

“We are seeing quite massive cuts to integration classes, to asylum counseling, but also to the really few already centers who give and who are specialized in therapy and trauma for refugees. And this is something that I find extremely worrying.”

“The Germans are very clear how they define integration and this is extremely harsh for people to follow,” says Langenbach. “They simply cannot work as a bricklayer or truck driver even if you have experience from your home country. If these men do not see a system where they are allowed to show what they can be worth given their labor to whomever, that is a weird situation… [They] simply do not understand the system and what we expect from them.”

“That leaves a person in an insecure feeling,” he ends.

Thousands of Afghans have traversed the treacherous mountain paths between Turkiye and Iran, evading border police while seeking refuge in secluded canyons and small villages. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Many Still Toiling in Pakistan

While many Afghans in Germany feel worried about the future possibility of being returned to Afghanistan under Taliban rule, thousands of others are still waiting for a chance to come to Germany in resettlement programs.

Since August 2021, when the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan, thousands of Afghans have come to Germany from Pakistan after promises from the German government through two special admissions programs.

Many have been anxiously waiting for months for approvals, and are waiting for the final green light to be resettled, but things are still far from certain. There is ambiguity around the program. On the German government’s page for the Federal admission program for Afghanistan, it states: “With budget negotiations being in progress, the program is currently focused on facilitating the departure of individuals who already have received approval for admission to Germany. These individuals’ departure is being actively supported by the German Government.”

DW reported in August that the program was ending.

An Afghan in the program who says he has been approved said that he and his family have been waiting for months for relocation to Germany. They still live in Pakistan, and do not have the final approval they need, which has brought extreme stress on his family. He says that people he knows in his accommodation continue to be rejected and have nowhere to go.

The process has become increasingly prolonged, with many applicants facing rejections and significant waiting periods for multiple years in Iran and Pakistan. There has been an enormous emotional and financial strain on families, with endless bureaucratic delays and no certainty. Many have sold everything in Afghanistan with the expectation that they would be starting new lives in Germany within a few weeks or months.

“Now it’s been more than a year in Pakistan, and they still have no interview and no final decision, and they are waiting with no guarantee,” he says.

“There was a woman in our accommodation with four members of her family who was rejected. She almost committed suicide the next morning when she received the news because she had nothing left in Afghanistan, and didn’t have the minimum amount of money to even pay for transportation to go back to Afghanistan. And when she asked for support or some clarification, nobody at the German embassy responded to her emails or calls,” he says.

A gravestone marked “Afghan” stands in a cemetery on the outskirts of Van, Turkiye, symbolizing the countless unmarked graves of Afghans and other asylum seekers who have perished while attempting to cross the mountains or Lake Van. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Despite the long wait and trauma, he remains hopeful about resettlement for his family. After more than five months of anticipation, he feels optimistic about getting on an upcoming flight, but frustration continues to mount.

The emotional toll is heavy; his family members, including his mother and wife, have become ill from anxiety and depression. He has often considered returning them to Afghanistan due to their distress, but that path is impossible for him after working with foreigners. Despite these challenges, he resolves to wait a little longer, holding onto the hope that their situation will improve and they will not have to take the step of illegally migrating to Europe.

While many Afghan refugees in Germany grapple with the political winds shifting, and the anxiety of possible deportation back to a perilous homeland, others waiting for their chance to come for the first time to a safer country remain hopeful, envisioning a future where they can build new lives. The latest terror attack in Magdeburg could tighten migration policy even further.