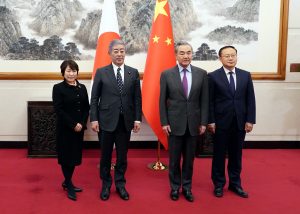

During his first official visit to China on December 25-26, Japanese Foreign Minister Iwaya Takeshi made an unexpected announcement. Japan will relax its entry requirements for Chinese nationals and grant ten-year tourist visas as part of a so-called Creating an Environment Conducive to Promoting People-to-People Exchanges initiative.

The statement came as a surprise on multiple fronts as the rationale for offering such unprecedented preferential treatment is unclear. China’s response was, essentially, valueless. The 10-year multiple-entry tourist visa to be provided by Japan to Chinese nationals was met with China offering a mere 15-day extension (from 15 days to 30 days) for Japanese visitors to China. Hardly a quid pro quo.

Such pandering by the Japanese government is bizarre given the current diplomatic backdrop. Since China enacted its “counterespionage” law in 2015, 17 Japanese citizens, including an Astellas employee last year, have been arrested and detained. As U.S. Ambassador to Japan Rahm Emanuel opined in 2023, “China says they’re open for business, but it doesn’t feel like it for the employees of Astellas, Bain & Co, Mintz, Capvision, and, now, Nomura. The list of companies targeted by police raids, arrests, and detainment is growing by the day, and foreign investment continues to slide by the week. When it comes to topic of ‘containing’ China, the PRC is in a class of its own.”

Apparently, the Ishiba administration thinks differently.

Furthermore, the announcement of the new visa program does nothing to deter ongoing and aggressive Chinese military deployments. Ironically, on the same day of the announcement of the new program, another Chinese buoy was reportedly found in Japan’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), 140 km southwest of the Japanese island of Hateruma, Okinawa Prefecture. The Japanese foreign minister’s ineffective appeal to his Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, bore no fruit, as a Chinese spokesperson later insisted that the buoy was within “Chinese jurisdiction,” “rational,” and “legitimate.” China will not acquiesce to Japanese demands for its removal. This is another example of China’s refusal to compromise in areas where its national interest is perceived to be significant. And this negative development only added to the Japanese government’s embarrassment against the backdrop of its staged closeness and pronouncement of two nations seeking ways to improve their relationship.

What is the rationale for the Ishiba administration’s deference to China? Is it post-war guilt, diplomatic virtue signaling, economics, or trade? Whatever the perceived gain, the reality is that Japan achieved nothing but the appearance of submission, alongside further national security challenges and a future social welfare fiscal burden.

The visa initiative is clearly not driven by any economic logic. The argument that a ten-year “tourist” visa is necessary to encourage tourism is entirely specious, when a three-month visa, as commonly offered by other nations, would suffice for any genuine sightseeing endeavor. The fact that Chinese visitors aged 65 and older are exempted from submitting proof of employment when applying for visas is also troubling. It opens Japan up to opportunistic medical tourism that will only further burden the already struggling Japanese health and social security systems.

The issue of medical “tourists” comes at a time when Japan’s demographics have deteriorated to hazardous levels, in which the numerical imbalance between young workers and retirees, and a historically low and declining birthrate, already make Japan’s social security and health systems fiscally unsustainable. These structural problems also create a drag on economic growth. Since 2000, Japan’s annualized real GDP growth was only 0.6 percent, while the U.S. economy grew at more than three times this rate, and the Chinese economy at ten times that of Japan. A perceived quick revenue fix from tourism will certainly not reverse such a long-run structural decline.

Another consideration is that of national security. The Cabinet Office report of December 23, 2024, revealed that Chinese nationals are now the biggest foreign buyers of Japanese land, particularly in areas near sites deemed sensitive to Japan’s security. An inability to adopt an effective national security legislative framework is seen in combination with a lack of urgency to address pressing domestic issues.

Rather than ushering in the new spirit of Sino-Japanese détente, the initiative appears to be a sign of Japan’s weakness that will likely only invite further Chinese aggressiveness. Such Japanese ineptitude illustrates that Japan may be freely taken advantage of, and this makes Japan less secure, not more.

As neither Japan’s prime minister nor foreign minister has yet visited the United States to meet with key members of the incoming Trump administration, Iwaya’s visit to China was seemingly timed deliberately. Instead of such ill-conceived forays directed toward a Sino-Japanese rapprochement, Japan’s diplomatic imperatives would have been better served by first shoring up its diplomacy and strategic security alliance with the United States as its sole ally. Stronger messaging toward the United States, to protect its interests, rather than essentially unilateral action toward a non-ally, would have been a better use of Japanese diplomacy. Additionally, Japan should be further advancing the nation’s embryonic security corporation with democratic nations such as the United Kingdom and Australia, with which it holds shared values, and institutions such as NATO.

The Japanese concessions, albeit perhaps well-intentioned, risk upsetting the delicate balance in terms of the security systems that have largely maintained peace in East Asia in the modern era. Japan’s pro-China moves risk further isolating Taiwan and could accelerate China’s territorial ambitions in the Taiwan Strait.

Japan, over recent years, has adeptly maintained functional diplomatic and economic ties with both China and Taiwan. The new pro-China policy could manifest a Japanese own goal where it may ultimately be forced to choose China over Taiwan.

Undoing the carefully crafted diplomacy of his predecessors shows the danger of a prime minister who has no strategic plan or long-term foreign policy goal. The pro-China approach appears to be policy made “on the fly,” yet it will create problems that, at best, may endure for years. At worst, the impact may prove to be both deleterious and irreversible.