On March 13, Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te accused China of a malign influence campaign to subvert Taiwan’s democracy and autonomy. In recent months, Taiwan has also been riven by a brewing constitutional crisis, political polarization, and even legislative brawls between Lai’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and the opposition Kuomintang (KMT) that controls the Legislative Yuan, Taiwan’s parliament. The founder and leader of the Taiwan People’s Party, which holds eight swing legislative seats and sides with the KMT opposition, was arrested on corruption charges in December.

Yet for all of the recent turbulence roiling Taiwanese politics, we must not lose sight of the great democratic strides that Taiwan has made over the last three to four decades. Taiwan, which remains critical to global semiconductor supply chains – producing almost 70 percent of the world’s chips and nearly all of the most advanced ones – is living proof that a democratic David can thrive in the shadow of an authoritarian Goliath.

An underappreciated source of success of Taiwan’s democratic emergence and resilience is its civil society, which has a rich history of student activism and mass mobilization for democracy. As Taiwanese must find new ways to defend democracy from Beijing’s sharp power, it is worthwhile recalling the lessons from earlier civil campaigns to promote democracy in Taiwan, especially the Wild Lily Movement that occurred this month 35 years ago as the Cold War in Asia was coming to an end.

Remembering Taiwan’s Wild Lily Movement

During the Cold War, both Taiwan and mainland China were ruled by personalist single-party authoritarian regimes. Both Taiwan’s KMT and China’s Communist Party (CCP) prevented free and fair national elections, repressed civil society, and engaged in heavy censorship. But since 1989-1990, Taiwan and China’s political regimes have evolved in very different ways, in part reflecting the failure of Tiananmen protests in China in 1989 and success of the pro-democracy Wild Lily Movement in Taiwan less than a year later.

From March 16 to March 22, 1990, the Wild Lily student movement mobilized in anticipation of the inauguration on March 21 of Lee Teng-hui, who had been elected president indirectly based on only the votes of the National Assembly. At the time, no new members had joined the National Assembly since the Republic of China retreated to Taiwan in 1949, and many students believed that it no longer represented the will of the Taiwanese people. Beginning with a small group of students from National Taiwan University, thousands of students and other supporters gathered at the Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall to protest the undemocratic election of this new president.

By 1990, Taiwan had begun partial political liberalization a few years before and allowed new political parties since 1987. However, martial law – the Temporary Provisions Against the Communist Rebellion enacted in 1948 – was still in place. President Lee thus had legal (if not moral) authority to repress the 1990 protests, much like his predecessor Chiang Ching-kuo had repressed the 1979 Kaohsiung incident. Instead, the Wild Lily movement marked the beginning of the end of the White Terror, the repressive period of KMT rule that ensured the suppression of political opposition.

The organizing committee of the movement made four key demands: (1) dissolve the National Assembly and create a new National Assembly infrastructure, (2) nullify the Temporary Provisions, (3) hold a National Affairs Conference, and (4) create a timetable for political reform, including direct presidential elections. Demonstrations and a student hunger strike led Lee to invite a group of 53 students to meet and negotiate. The protestors agreed to leave the square after Lee agreed to address their demands.

Democratic Development in Taiwan since 1990

Lee quickly made good on his promises. In the wake of the Wild Lily Movement, Lee initiated negotiations with the DPP, which led to the National Affairs Conference (June 28 – July 4, 1990) that paved the way for direct elections to the National Assembly in 1991 and Legislative Yuan in 1992. The Temporary Provisions were lifted in 1991. As Lee’s first term as president concluded, Taiwan held its first direct presidential election. Despite KMT splits, Lee won re-election in 1996, buoyed by nationalist credentials and backlash to China’s intimidation with missile tests.

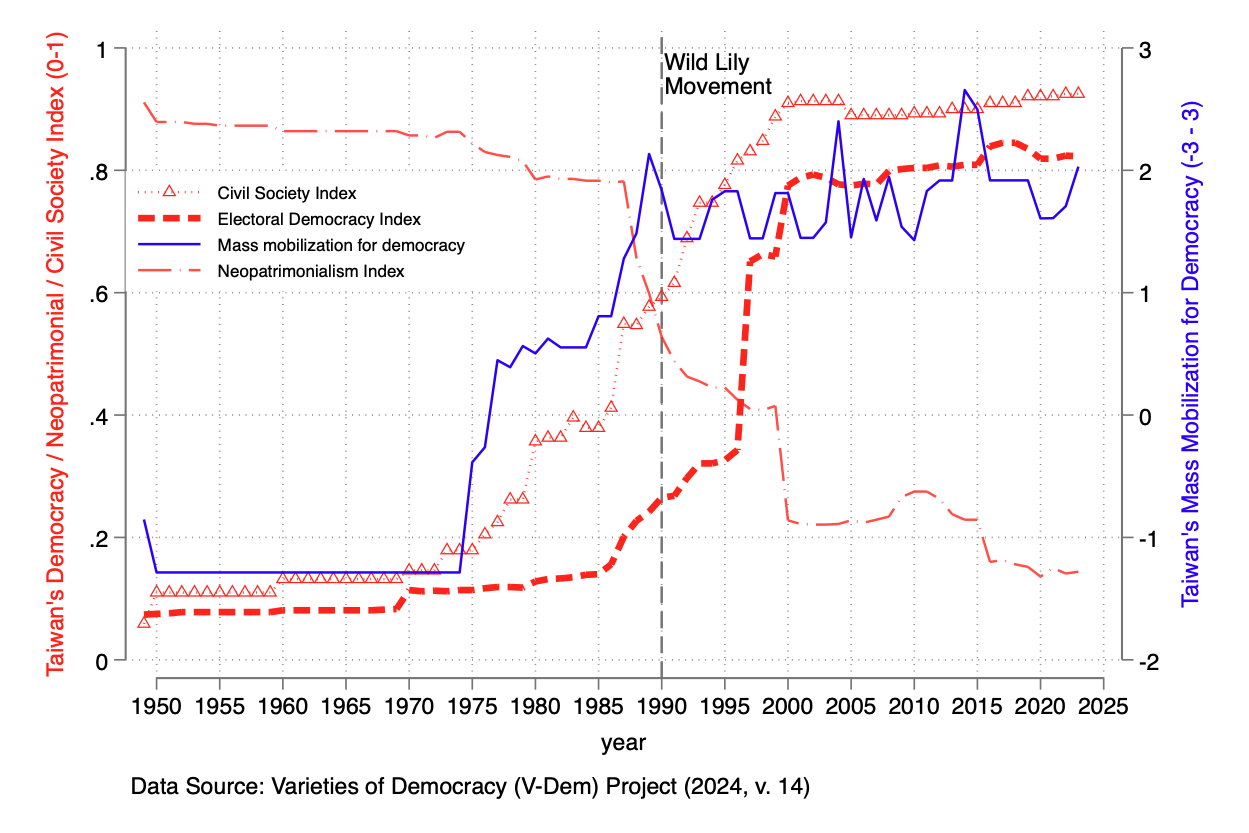

Data from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project (see Figure 1 below) show the importance of a strengthening civil society and rising mass mobilization for democracy – including the Wild Lily Movement — in Taiwan’s democratic breakthrough in the 1990s. The rise of Taiwan’s electoral democracy was mirrored by the rapid decline of neopatrimonialism.

Figure 1: Democracy, Civil Society, and Mass Mobilization in Taiwan, 1947-2023

Taiwan’s democratic transition was completed in 2000, when DPP candidate Chen Shui-bian won presidential elections – bringing an end to more than five decades of KMT rule on the island. In the decades since, Taiwan has seen improved human rights protections and continuing democratic deepening and peaceful transitions of power.

From Wild Lilies to Wild Strawberries and Sunflowers

Taiwan’s civil society has continued to be a force for democratic consolidation in recent years. In 2008, the student-led Wild Strawberry movement used a month-long sit-in to protest the visit to Taiwan of a high-level Chinese diplomat and restrictions on protest. In 2012, the “Wild Strawberry generation” protested Chinese influence over Taiwan’s media.

Starting on March 18, 2014, near the 14th anniversary of the Wild Lily movement, hundreds of university students broke into Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan to protest a hastily advanced trade agreement between Taiwan and China. The KMT-backed trade agreement, known as the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA), would have lifted trade restrictions on the service industry, including sensitive sectors like telecommunications, banking, and publishing. The students made four demands: (1) an apology for the “black-box” operation of forcing the agreement through the legislature, (2) a constitutional conference, (3) rejecting the CCSTA, and (4) a bill to monitor agreements between Taiwan and China.

After the government agreed to a hearing on April 10, the students left the Legislative Yuan. This Sunflower Movement blocked the CSSTA and birthed a “sunflower generation” determined to protect Taiwan from threats to democracy.

With Beijing insisting that Taiwan is a part of China and repeatedly emphasizing its intent to reclaim the island – perhaps by force – democracy in Taiwan must remain strong. Student activism reflected in the likes of the Wild Lily and Sunflower movements plays an important role in the protection of Taiwan’s sovereignty and democracy. Last summer, Taiwan saw renewed protest over a controversial KMT-backed “contempt of parliament” bill. The lasting legacy of the Wily Lily Movement suggests that such mass mobilizations, rather than a source of chaos and unrest, are integral to democratic resilience in Taiwan.

CCP leader Mao Zedong famously launched his Hundred Flowers campaign in the late 1950s, with the slogan “Let a hundred flowers bloom, and a hundred schools of thought contend.” That level of freedom of speech and assembly has not yet been reached in China, but Taiwan shows that “flower power” can indeed be an engine of democracy.