In January 2025, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld U.S. legislation that would effectively ban TikTok, citing national security concerns over its Chinese ownership. This legal ruling set off a wave of uncertainty for the millions of American users who rely on the app for entertainment, connection, and even business. Immediately after President Donald Trump took office, he pushed back the total ban, instead instituting a 75-day probation period, wherein TikTok has to find a U.S.-based buyer and any violations of the terms, particularly relating to data privacy and governance, could lead to another shutdown.

But in the midst of this chaos, another app emerged: RedNote, also known as Xiaohongshu on the mainland. The Chinese platform quickly gained traction among TikTok’s displaced users. However, what appeared to be a natural shift for users was, in fact, a carefully orchestrated relocation backed by an apparent influence campaign, which raises significant concerns about digital privacy, influence, and security.

The TikTok ban was part of a broader effort by the U.S. government to protect national security. Critics argued that the app, owned by the Chinese company ByteDance, could potentially share sensitive user data with the Chinese government. Although this ban only affected the U.S., other countries had already taken similar measures, such as India, which blocked TikTok back in 2020.

In response to the U.S. ruling, millions of TikTok users found themselves searching for alternatives. This provided a prime opportunity for RedNote to fill the void left by TikTok’s abrupt departure. Influencers and online personalities began promoting RedNote as the next-best option.

While many assumed the migration to RedNote was a natural consequence of TikTok’s ban, it was, in fact, the result of a well-coordinated influence campaign driven by China-backed entities. Here’s how it unfolded.

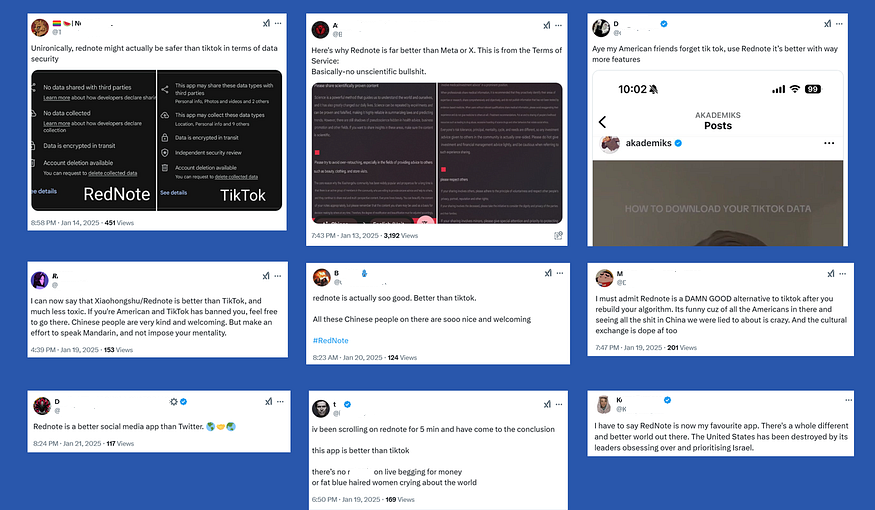

Influencers, many of whom were already embedded in China’s extensive digital ecosystem, began pushing RedNote as a safer, more secure alternative to TikTok. Their campaigns often featured messages of data privacy and personal security, playing into the fears stoked by the TikTok ban. These influencers leveraged their reach to frame RedNote not just as an app, but as a movement – one where users could reclaim control over their digital lives.

Tweets promoting the RedNote app during the period from Jan. 13-20, 2025.

Analysis of social media activity during this time revealed a concerted effort to highlight RedNote’s supposed advantages over TikTok, including its data privacy policies, which were framed as more favorable compared to TikTok and U.S. counterparts like Instagram. In fact, Lemon8, another Chinese app, was also part of this narrative but received far less promotion.

The trend started on January 13, a week before the TikTok ban was set to take effect. By January 14, global tweet activity for the hashtags #RedNote and #TikTokRefugee reached its peak. This surge aligned with escalating concerns surrounding a potential TikTok ban in the United States, which has created uncertainty among the platform’s user base. The fear of losing access to TikTok was used as an opportunity to drive influence to RedNote, with a sudden rise in influencers calling themselves “TikTok refugees” and heavily promoting RedNote.

The rise of RedNote, a Chinese app similar to TikTok, is closely tied to the ongoing digital battle between the U.S. and China. RedNote’s Chinese name, Xiaohongshu, which translates to “Little Red Book,” directly references a symbol of the Chinese Communist Party. Despite this, RedNote was marketed as an ideal replacement for TikTok, with influencers applying disinformation tactics to downplay the app’s data security issues.

The influencers that initially promoted the app fall into two categories: pro-China influencers and bot-like behaviors. The pro-China accounts frequently used Mandarin phrases like “Ni Hao” (hello) in their posts and often promote Chinese government policies, Chinese technology, and CCP platforms. This suggests the coordinated promotion of RedNote was also in line with CCP’s ambitions.

Bot activity was evident as well, with accounts exhibiting high tweet volumes in short timeframes, repetitive hashtags, and minimal genuine engagement. The total view count of the top 20 users posting about RedNote was around 22.3 million. (The top 20 is based on number of tweets using the hashtags #TikTokRefugee and #RedNote.) In total, these 20 users posted 277 times using those hashtags from January 1 to January 17, with the top five users all posting more than 20 times apiece.

Analyzing the timeline of the tweets provides more evidence of this coordinated campaign. On January 14, a significant peak was observed, with over 1,100 tweets using the keyword “Xiaohongshu.” This coincided with a surge in RedNote-related posts and was likely a result of influencer-driven or bot-assisted campaigns. The accounts involved in these tweets were largely from the same influencers, such as @CarlZha, @thinking_panda, and @LQniupitang, many of whom are known for pushing pro-China narratives. These same influencers also played pivotal roles in promoting RedNote, further linking the two hashtags and reinforcing the connection between RedNote and China’s digital influence strategy.

From the follower distribution of the accounts posting about RedNote, it can be seen that 45 percent of users posting with these hashtags have more than 2,000 followers. This indicates that larger accounts with significant influence were the key marketers of the hashtags. Most probably, these users were fundamental to changing the narrative, fostering visibility, and hastening the public focus on RedNote.

On Instagram, the hashtag #TikTokRefugee experienced a sharp rise on January 15, with over 830 posts. The uptick in activity on Instagram coincided with similar spikes on Twitter, further amplifying the notion that a digital influence campaign was actively pushing RedNote as the next “safe haven” for displaced TikTok users. A similar drive promoting RedNote was being done on other social media apps like Facebook, Weibo, and TikTok itself.

As a result of this drive, there was a surge in downloads of RedNote in the United States in the same timeframe, from January 13 to 16. If this was a CCP-backed influence campaign, it was a massive success. And it was followed by a wave of articles in Chinese state media praising the friendly exchanges between Chinese and American users of RedNote.

While RedNote was marketed as a safe alternative to TikTok in this viral social media campaign, the underlying reality is far more troublesome.

Both TikTok and RedNote have security issues and privacy flaws. Under Chinese law, specifically the National Intelligence Law of 2017, all Chinese companies, regardless of where they operate, are required to cooperate with the government in intelligence-gathering activities. This means that both apps are legally bound to share user data with the Chinese government if asked. This raises significant concerns about the security of users’ data. RedNote, despite its appeal as a supposedly more secure “TikTok alternative,” operates under the same legal constraints as its predecessor, making it equally susceptible to government surveillance. Users who flocked to RedNote in search of privacy were unknowingly accepting the same risks they sought to avoid.

As the Chinese government’s influence over its tech giants continues to grow, it is clear that RedNote is not just an app vying for market share. Rather, it is part of China’s broader strategy to export its digital infrastructure globally, thereby expanding control over user data and influencing global narratives. RedNote’s sudden surge in popularity is not merely the result of consumer choice; it’s a strategic maneuver in the digital battle between China and the West.

RedNote’s meteoric rise also raises questions about the broader implications for user privacy. Both TikTok and RedNote have been accused of breaching privacy regulations and mishandling user data. Similarly, in Europe, TikTok and other Chinese apps like AliExpress have been accused of transferring Europeans’ personal data to China, violating privacy laws. Other Chinese apps, such as WeChat, Shein, and Temu, are subject to similar concerns about their data collection practices and their potential to share data with the Chinese state.

These concerns are not just hypothetical. Reports of data breaches involving Chinese apps have surfaced over the years, with allegations that user data has been passed to the Chinese government for surveillance purposes. The lack of transparency around RedNote’s data security practices only deepens the suspicion that users may be unknowingly participating in a digital ecosystem that is heavily monitored and controlled by the Chinese state.

China’s internet censorship system – known as the “Great Firewall” – blocks foreign platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. As a result, apps like WeChat, Sina Weibo, and Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok) dominate the digital space within China, all of which are subject to government oversight and censorship. In contrast, Chinese companies like ByteDance have found success in international markets by marketing their apps as symbols of innovation and freedom. The rise of RedNote, underpinned by a digital influence campaign, represents a new phase in China’s efforts to export its tech infrastructure and extend its reach into global markets.

As the U.S. and China vie for dominance in the digital sphere, the question of data security, national sovereignty, and digital influence is becoming increasingly important. India has been particularly vocal about banning Chinese apps, including TikTok, over concerns about privacy and national security. Chinese influencers and state-backed accounts have accused India of parroting the U.S. narrative and claimed that India’s position is driven by foreign interests. These accusations reflect a broader effort by China to discredit countries that take action against Chinese apps, further promoting a narrative that frames these countries as unreliable or biased. Indian media coverage of RedNote has been criticized by Chinese netizens for misrepresenting the app, while some Chinese users even attempted to spread negative stereotypes about India through the app.

Perspective hacking, as seen in the pro-RedNote campaign, manipulates public perception, threatening governance and eroding trust in digital institutions. By distorting the truth and shaping narratives to align with geopolitical objectives, such campaigns create an environment where disinformation thrives. Nations engaging in these tactics set a dangerous precedent, subtly eroding democratic reasoning and suppressing dissent.

This is not just a privacy or national security issue; it strikes at the core of democracy and freedom. If left unchecked, the digital sphere could become a battleground where manipulation replaces genuine discourse, leaving no room for independent thought or democratic decision-making. Nations must recognize this challenge and act decisively to protect the integrity of governance, free speech, and public trust.