An idyllic island in the Gulf of Thailand has recently become a subject of contention between nationalists in Thailand and Cambodia, derailing negotiations over the joint exploitation of offshore gas reserves.

Koh Kood (or Koh Kut) is a popular holiday hotspot for foreign tourists to Thailand, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors each year. But Cambodian activists and nationalists have recently reignited a decades-old territorial dispute, claiming that the island partly belongs to Cambodia.

Hun Manet, the prime minister of Cambodia, recently waded into the debate, publicly stating that its claims over Koh Kood, which is referred to as Koh Kuch in Khmer, had not yet been lost.

The disagreement over Koh Kood dates back to the era of French colonial rule in Indochina. In 1904, Thailand, then called Siam, ceded the island to France, along with the nearby port of Trat and other adjacent islands. In the Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1907, these territories were then retroceded to Siam in exchange for large territories in western Cambodia.

However, Cambodia has never fully accepted Thai sovereignty over Koh Kood. In 1972, Phnom Penh released an official map and normalized its continental shelf with a decree that asserted a claim over the southern part of Koh Kood.

Koh Kood is internationally recognized as part of Thailand, and the Thai government claims the island on the basis of the 1907 treaty, as well as under international maritime law.

The fourth-largest island in Thailand, Koh Kood is located in Trat province in the Gulf of Thailand, near the maritime border with Cambodia. Although claims over its ownership linger, Koh Kood’s laid-back atmosphere, marked by soothing beaches, luxury resorts, and turquoise waters, masks any signs of tension on the island.

But despite the island’s placid nature, Cambodian claims to the island are getting louder.

Over the past two years, diaspora groups around the world have held protests over Koh Kood, holding recent demonstrations in Australia, Canada, France, South Korea, Switzerland, and the United States.

Mu Sochua, a Cambodian politician and president of the U.S.-based Khmer Movement for Democracy, says that Cambodian diaspora communities are demanding that the Koh Kood dispute be heard by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, Netherlands.

“Based on official documents, part of the island belongs to Cambodia,” Mu Sochua told The Diplomat, referring to the 1907 treaty.

Sochua said that her group would present its recommendations for Koh Kood to Cambodian King Norodom Sihamoni and the Cambodian government via the Cambodian Embassy in Washington, D.C., on May 10. It hopes that the government will bring the case to the ICJ.

However, Tita Sanglee, a Diplomat columnist and associate fellow at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, says that Cambodia’s claims over Koh Kood are contentious.

“Cambodia’s claim was rooted in a different interpretation of the said treaty,” she said. “It should be noted that the 1907 Treaty, like other treaties of its time, intended to address land, not maritime, boundaries. This is why the Cambodian interpretation is controversial.”

Offshore Bounty

The dispute over Koh Kood resurfaced in 2024 when misleading posts on the social media app TikTok showed Thailand transporting military vehicles for exercises close to the island. The video turned out to be fake, as did other rumors claiming Thai and Cambodian military forces had been involved in a skirmish near Koh Kood.

This happened even as Thailand and Cambodia announced their intentions to reopen negotiations over their maritime border in the Gulf of Thailand, which has remained undemarcated since the Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1907. The disputed area, known as the Overlapping Claims Area (OCA), totals around 27,000 square kilometers and is believed to contain underwater resources, including significant natural gas reserves.

In 2001, the two sides signed a Memorandum of Understanding to act as a framework for negotiations over the OCA. Then Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra urged both Thailand and Cambodia to resolve the dispute so that they could benefit economically from the potential energy resources in the Gulf, but negotiations petered out after Thaksin’s removal in a military coup in 2006.

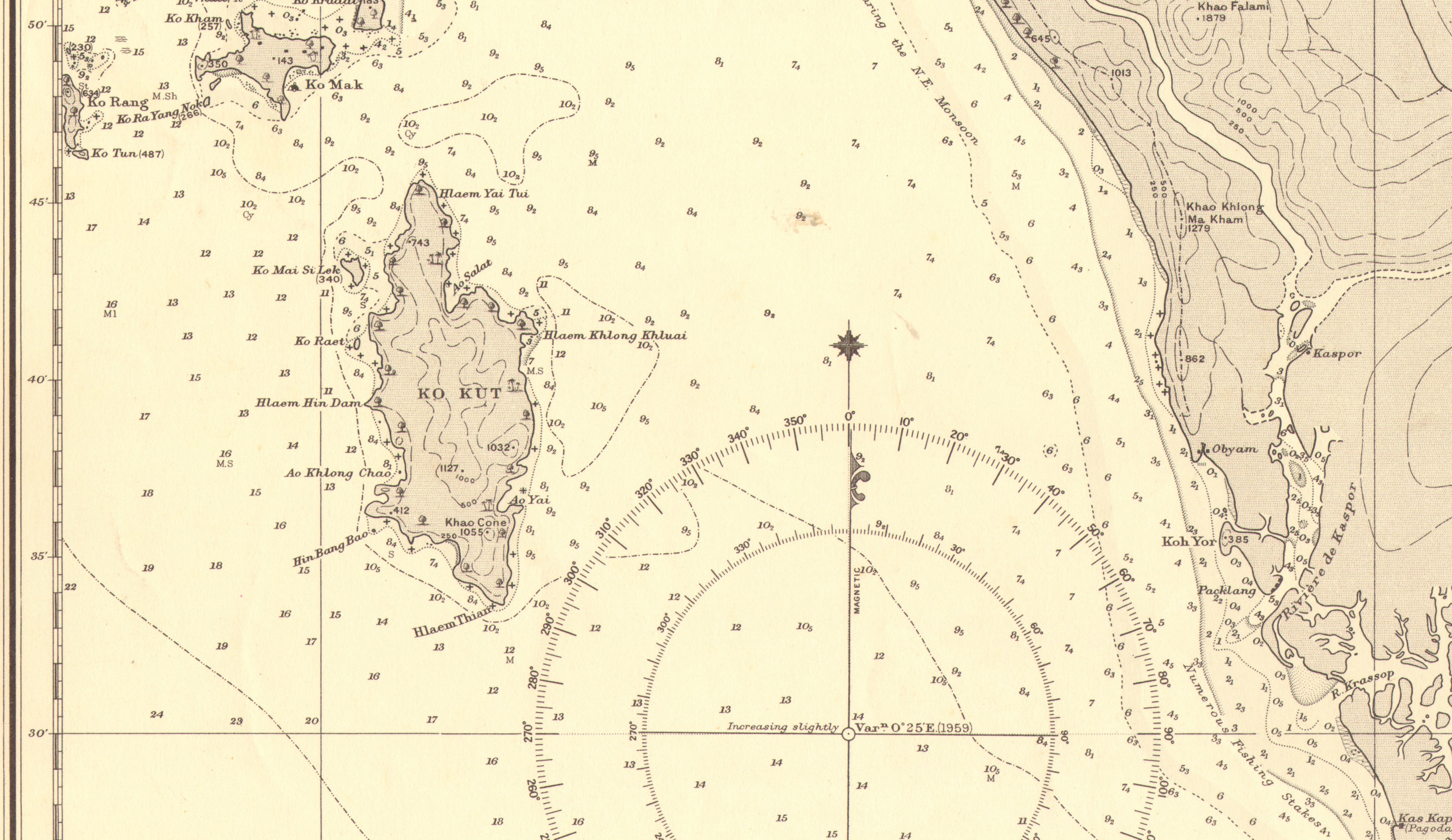

A detail of a British Admiralty Chart of the Gulf of Thailand published in 1957, which shows the island of Koh Kut. (United Kingdom Hydrographic Office)

Twenty-four years on, Thaksin’s party, Pheu Thai, is back in power, and is keen to resolve the dispute over the OCA as part of its broader economic focus. Thailand’s economy grew slower than anticipated in 2024, and reviving economic growth was one of Pheu Thai’s major promises during the 2023 general elections – one that remains unfulfilled so far.

With Cambodia also determined to boost its economy, and the world’s growing demand for energy, both sides had an incentive to resume the talks over resource sharing.

But the resumption of the talks over the OCA awakened the concerns of Thai nationalists long opposed to Pheu Thai, who claimed that settling the OCA could lead Thailand to cede Koh Kood to Cambodia. This prompted reactions from Cambodian nationalists, who have reasserted their own dormant claim that the southern part of Koh Kood lies within the lines of the OCA.

“The dispute manifesting itself today is because the Thai and Cambodian governments, for the first time in forever, both expressed peak political will to resume maritime boundary talks,” Tita said. “Both sides want to utilize untapped fuel fields as they face rising import costs for energy.”

Facing nationalist pressure from each side, the OCA negotiations have since stalled and the two governments have been forced onto the defensive. Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra’s administration has maintained – correctly – that ongoing maritime boundary discussions do not affect the status of Koh Kood, which was ceded to Thailand in 1907. In November, the Thai leader clarified that Koh Kood belonged to Thailand and that her government “is committed to safeguarding Thailand’s territory entirely and ensuring the happiness of the people.”

In Cambodia, Hun Manet was forced to address concerns over Koh Kood during an event in Cambodia in March.

“Our land and water borders have not been negotiated yet. We are still negotiating,” he said. “We have our demands from 1972. I would just like to clarify that the water border, Koh Kut, this overlapping area, some people are trying to get us to sue, saying that we have lost it. It has not been lost anywhere. The water border has not been negotiated or agreed upon yet. We are still demanding it, but it has not been closed.”

Tita said that Manet’s “strong” statement could impact relations between Thailand and Cambodia.

“I think Hun Manet felt pressured to make a strong statement,” she said, adding that he could not afford to allow Cambodian diaspora groups and opposition figures to set the political agenda. But she added that his words “are bound to stir up bilateral tensions,” especially in the context of recent tensions along the Thai-Cambodian land border.

In February, a group of Cambodian soldiers visited the Prasat Ta Muen Thom, an Angkorian temple that sits in Thailand’s Surin province, close to the border with Cambodia’s Oddar Meanchey province, and began singing the Cambodian national anthem, prompting an official reply from the Thai army.

The following month, Thai soldiers claimed that they observed their Cambodian counterparts occupying an area along the border in Sa Kaeo province. Cambodian soldiers were reportedly pointing and acting aggressively toward the Thai soldiers, prompting anger online from Thai nationalists.

Neither side wanted it to be this way. Despite their conflicting comments on Koh Kood, Paetongtarn and Manet are said to have a good relationship, while their respective fathers, Thaksin Shinawatra and Hun Sen, are known to be close. Manet has been prime minister since Hun Sen stepped down in 2023, after leading Cambodia for nearly four decades, while Paetongtarn took power last year after her predecessor Srettha Thavisin was dismissed from office.

Because of this, Hun Sen, who many believe still to be directing Cambodian foreign policy from his position as president of the Senate, would rather negotiate with Thailand than fight over Koh Kood, one former Cambodian politician says.

“Any attempt to recognize Cambodian claims to Koh Kood could be seen as a concession to Cambodia and could be opposed by nationalist groups in Thailand,” said Um Sam An, a former lawmaker for the banned opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party. “Thaksin Shinawatra is the god brother of Hun Sen. So, the prime minister of Cambodia doesn’t want to sue Thailand over Koh Kood to the International Court.”

He added that Hun Sen and Thaksin “just want to share benefits of gas and oil in overlapping area among the two families.”

The very closeness of the relationship between the two families has raised issues over transparency around the issue of Koh Kood. Mu Sochua says that for this reason and others, the 2001 MOU should be canceled.

“We are very concerned about the close family ties between the Hun and Shinawatra families and the lack of transparency. We want the cancellation of the 2001 MOU that involves the overlapping zone, as Cambodia at that time excluded Koh Kut,” she said.

A Legal Solution?

Should an agreement on maritime boundaries fail to materialize between Bangkok and Phnom Penh, as now seems likely, could an international court hearing be a feasible means of resolving the claims over Koh Kood?

After all, Cambodia and Thailand have been here before.

Between 2008 and 2011, Thailand and Cambodia became entangled in a minor border conflict over the area around Preah Vihear temple, an 11th century Angkorian ruin on the border lines of northern Thailand and Cambodia. Although the ICJ ruled in 1962 that the temple belonged to Cambodia, the revival of the dispute led to heightened bilateral tensions and scattered clashes along the border in which more than a dozen Thai and Cambodian troops were killed. In 2013, the ICJ affirmed Cambodia’s ownership of the temple.

These rulings have given Cambodian advocates confidence that the ICJ would rule similarly in the case of Koh Kood.

“We got Preah Vihear temple back from Thailand in 1962 through ICJ,” said Um Sam An. “We want the government to do the same thing. Thailand worries that they will lose again at the International Court, the same as Preah Vihear’s case.”

But Tita believes a court case may not be as beneficial as some Cambodians think.

“Many Cambodians seem to advocate for an international court case, and past records have shown Cambodia to be very good at playing the court game,” she said.

But she added that Thailand’s legal claims were much more solid here than in the case of Preah Vihear. “I don’t see how going to international court would benefit the Hun Manet government,” Tita said. “Would Cambodia really risk exposing its weaker legal claims and potentially compromise access to lucrative undersea resources from joint development negotiations?”