As the U.S. and Taiwan deepen their security cooperation, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have become a critical frontier for integrated deterrence. In today’s Indo-Pacific security environment, where deterrence hinges on distributed capabilities and resilient supply chains, Taiwan is redefining its defense strategy through UAVs, commonly called drones. Far from being peripheral, drones are emerging as a cornerstone of Taiwan’s operational doctrine and industrial policy. The strategic logic is clear: Taiwan’s drones are not just about national survival; they offer the United States a combat-ready, industrially capable partner in the most contested theater of 21st century geopolitics.

Taiwan’s drone strategy is shaped by three core objectives: (1) integrating autonomous systems into a layered, survivable defense posture; (2) building secure, scalable, and democratic drone production capacity; and (3) aligning industrial and operational frameworks with U.S. and allied priorities.

This article is an excerpt from an upcoming report on U.S.-Taiwan drone cooperation by the Research Institute for Democracy, Society, and Emerging Technology (DSET), a national think tank founded by the Taiwanese government and based in Taipei, Taiwan. The report draws on DSET’s interviews with Taiwanese stakeholders in the drone supply chain, including leading drone companies.

The following sections outline Taiwan’s phased UAV doctrine, current capability gaps, industrial mobilization strategy, and concrete opportunities for U.S.-Taiwan collaboration. Together, these elements form the backbone of a strategic partnership that strengthens deterrence before conflict.

Drones in Doctrine: A Three-Phase Battlefield Strategy

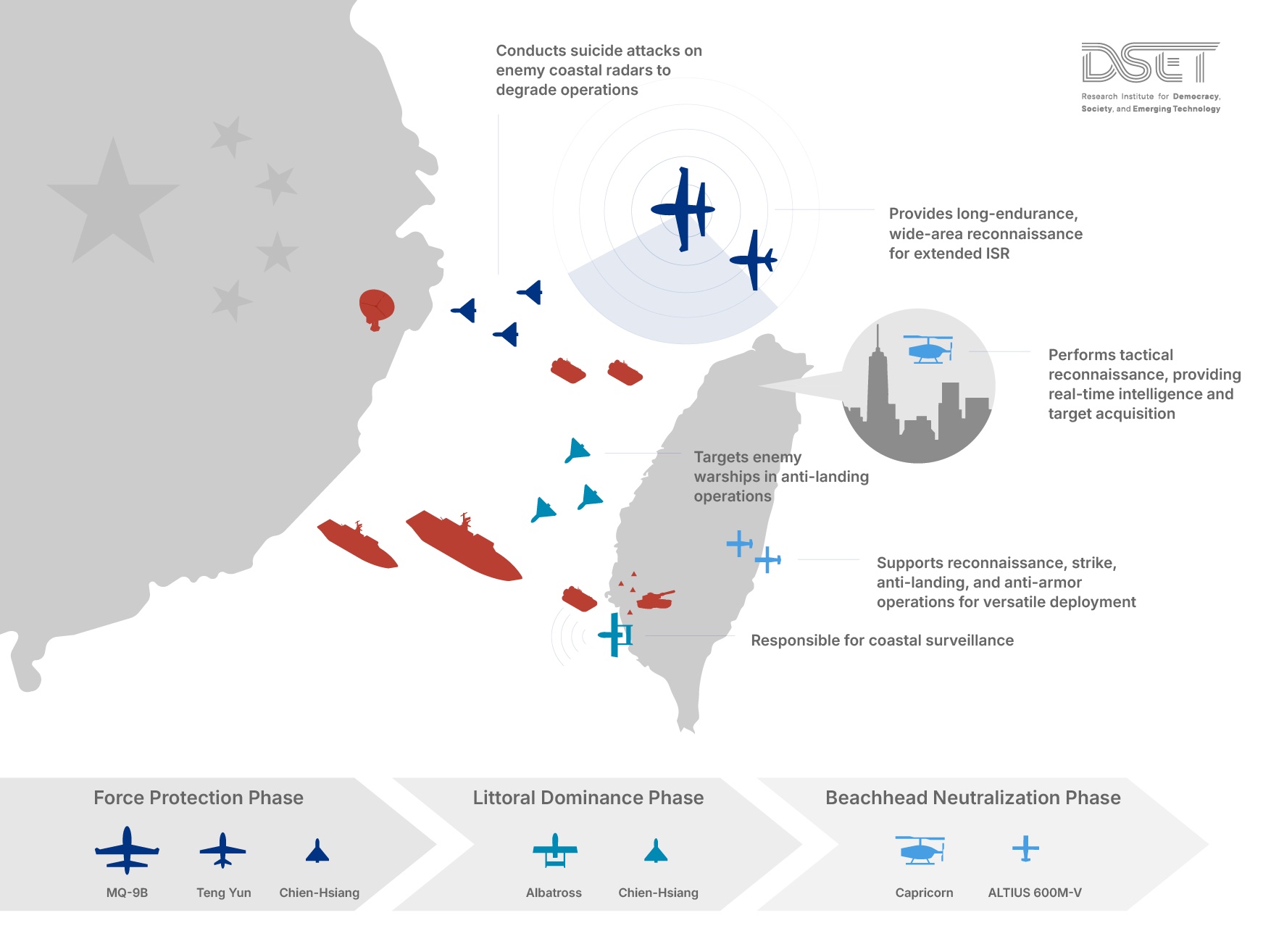

Taiwan’s Overall Defense Concept articulates a phased defense model: force protection, littoral dominance, and beachhead neutralization. Within this framework, UAVs play a central role in extending the reach of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities, degrading adversary systems, and sustaining combat operations under electronic attack.

In the force protection phase, Group 4-5 UAVs such as the MQ-9B and Teng Yun provide persistent ISR, enabling early warning and resilient command-and-control (C2) in contested environments. During littoral dominance, Taiwan employs Group 2 and 3 systems – such as the Albatross and Chien-Hsiang – to conduct electronic warfare and suppress coastal sensors. Finally, in the beachhead neutralization phase, attritable UAVs like the ALTIUS 600M-V and Capricorn execute precision strikes on landing forces and feed real-time targeting to ground units.

As illustrated in Figure 1, this doctrine leverages the logic of attritability, redundancy, and mission-tailored deployment – mirroring elements of Ukraine’s battlefield success and aligning with U.S. concepts like the Replicator Initiative and “Hellscape” architecture.

Mapping the Fleet: Progress and Pain Points

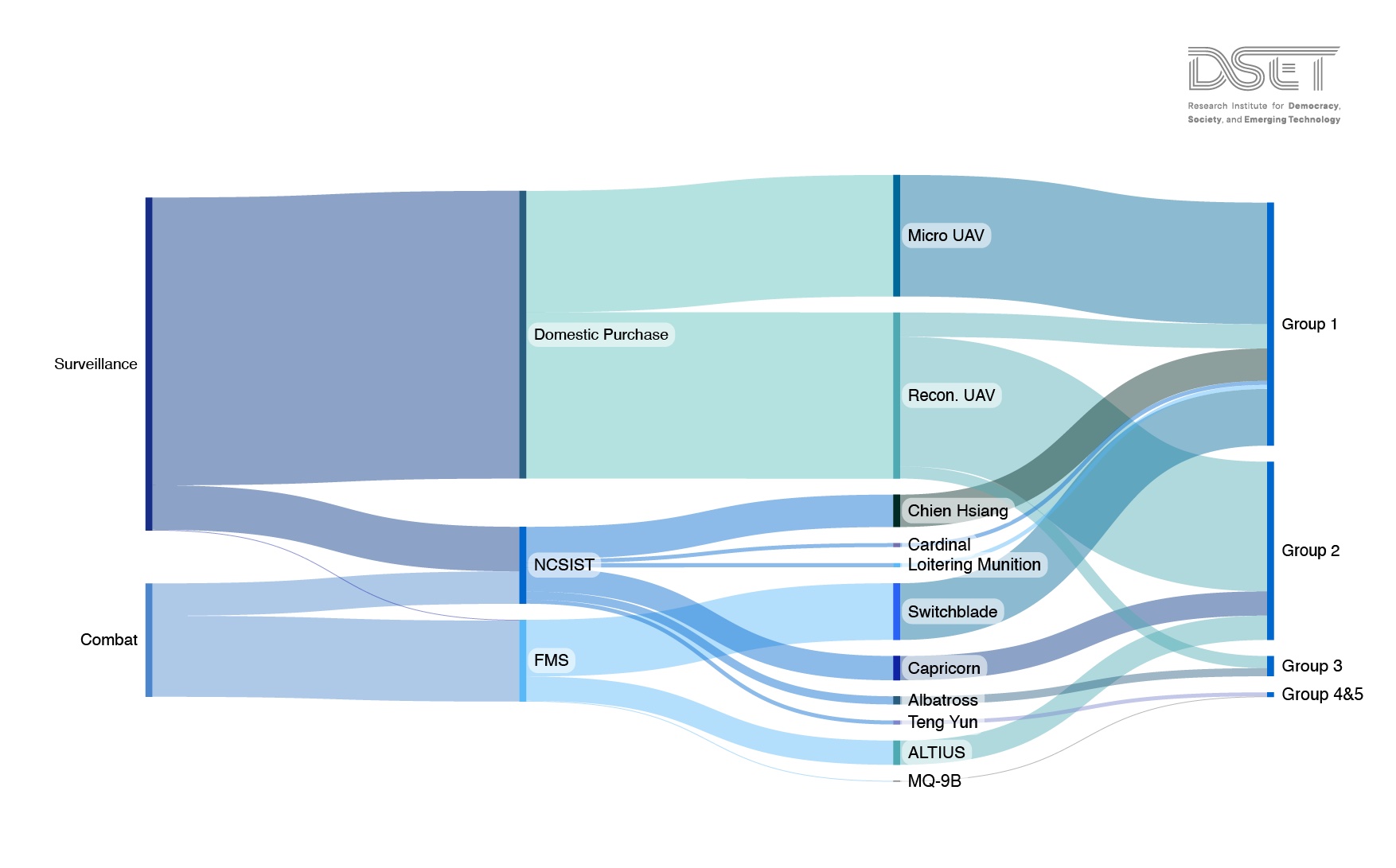

Taiwan’s UAV fleet is sourced through three primary channels: the state-owned National Chung-Shan Institute of Science and Technology, private domestic manufacturers, and U.S. Foreign Military Sales. Platforms range from commercial ISR quadcopters to high-end strike drones.

As detailed in Figure 2, Taiwan’s systems span the U.S. group classification framework, but operational gaps remain in Group 3-5 strike platforms, loitering munitions, swarm ISR systems, and autonomous targeting. These gaps reflect broader challenges identified in Taiwan’s defense community, including insufficient domestic production of key UAV components such as flight control chips, vision sensing chips, and secure video transmission modules. Despite significant research and development (R&D) investments, Taiwan’s domestic industry still faces cost disadvantages compared to Chinese suppliers and remains reliant on foreign parts for critical systems.

To meet these challenges, Taiwan has set a 2028 target of fielding 700 military UAVs and 3,000 dual-use drones. Achieving this requires not just procurement but a full-spectrum industrial mobilization and focused support for building indigenous component capacity.

Building the Arsenal: From Concept to Capacity

Taiwan’s UAV industry is advancing under a unified national strategy centered on three priorities: information security, aviation safety, and defense readiness. Coordinated by the National Development Council and supported by the Vice Premier’s office, the plan aims to achieve $30 billion New Taiwan dollars in annual production value and scale to 15,000 units per month by 2028.

This initiative will unfold in two phases. Phase I focuses on foundational technologies: secure flight control chips, SDR modules, AI-enabled ISR software, and MIL-spec testing. Phase II emphasizes production scale-up, democratic supply chain integration, and export readiness. The government has launched targeted R&D subsidies for key UAV components, prioritizing development in three critical chip categories and two core software layers.

However, implementation challenges remain. Strategic misalignment between government policy and industry capacity has slowed progress. As one senior executive from Taiwan’s UAV sector explained during interviews conducted by DSET researchers, “Decoupling from Chinese components is Taiwan’s opportunity – but we are not the only ones who can do this. Our advantage lies in our flexibility: if there are orders, we can deliver volume.” Larger firms push for deep specialization in advanced chips, while smaller companies advocate broader subsidy distribution. International demand remains uncertain as wartime-driven orders fluctuate, and firms face regulatory hurdles including strict Know Your Customer requirements for dual-use drone exports. To stabilize the industry, stakeholders are urging increased military procurement and more robust international cooperation mechanisms.

Taiwan’s strategy emphasizes “three chips and two software”: resilient hardware and secure digital platforms. These include GPS-independent navigation, encrypted communication, and NATO-aligned airworthiness standards. The Chiayi UAV Industrial Park serves as the anchor for this industrial buildout and is central to Taiwan’s ambition of becoming a regional drone manufacturing hub.

From Readiness to Reciprocity: What Taiwan Offers – and Seeks

Taiwan’s value proposition is straightforward. It offers a defense-ready drone ecosystem mapped to its three-phase operational doctrine, with mission-aligned UAVs – from ISR to loitering munitions to saturation-strike platforms – tailored for frontline Indo-Pacific use. Its production infrastructure is real and scaling, and its supply chain is secure, transparent, and non-red. Taiwan also brings a legacy of indigenous UAV development dating back to the 1970s, with lessons learned from recent procurement initiatives and public-private collaboration models. The September 2022 commitment to procure 3,000 UAVs signaled a turning point, demonstrating Taiwan’s serious investment in building industrial scale.

What Taiwan seeks is focused collaboration: joint UAV platform development tailored to frontline mission roles, streamlined technology transfer mechanisms that prioritize IP protection and encryption safeguards, and operational integration into U.S. Indo-Pacific logistics and deterrence planning. As emphasized by a systems integrator interviewed as part of DSET’s industry engagement, “What we hope for in Taiwan-U.S. collaboration is market access and technology sharing – especially in optical payloads and data transmission.” Taiwan also seeks formal inclusion in Blue UAS and other allied drone architecture frameworks.

As summarized in Table 1, Taiwan’s is not asking for open-ended assistance. It is making a reciprocal offer: to co-produce, co-develop, and co-defend.

Conclusion: The Window for Action Is Now

Taiwan’s drone strategy is not a speculative vision. It is a doctrine-driven, industry-enabled framework grounded in survivability, scalability, and partnership. It complements U.S. priorities in the Indo-Pacific by offering a forward-positioned, technologically credible, and operationally aligned partner.

The success of this strategy depends on deeper institutional frameworks and mutual commitment. Taiwan’s position as a hub of semiconductor and smart systems innovation enables it to shoulder greater responsibilities in defense tech. At the same time, U.S. political will and streamlined policy frameworks – particularly around International Traffic in Arms Regulations compliance and R&D funding – are essential to unlocking the full potential of this partnership.

Through joint UAV development, the U.S. and Taiwan can create a resilient, scalable uncrewed systems architecture that enhances deterrence, reduces allied risk, and complicates adversary planning. This is not about aid; it is about allied burden-sharing before the crisis. Taiwan stands ready to partner on the future of drone warfare. The question is whether the U.S. will seize this opportunity and build on it through sustained, next-phase integration.