When the audio clip of Ekramul Haque being shot dead on May 26, 2018 went viral online, it did two things.

First, it put on record the horrific reality of Bangladesh’s extrajudicial killings.

A wailing wife and children hearing their husband and father being shot dead on the other end of the line, the repeat gunshots by a remorseless paramilitary unit, and the groans of an innocent man begging for his life, telling his killers they’ve got the wrong guy: It’s a set of sounds that once played, just can’t be forgotten. (The audio clip is available here, but be warned: its contents are disturbing).

Second, the tape has, for the first time, made the Bangla government set up a formal commission of inquiry into an unlawful killing by law enforcement.

As per official numbers, in barely two months spanning April and May 2018, 157 people have been gunned down by the police and paramilitary in what they term as “crossfire.” Scores more have been picked up for questioning and then disappeared or detained indefinitely without charge.

The Killing of Ekramul

“Ekram was called on his phone by the local police and asked to come discuss a case,” an aide of the police commissioner recounted. “He was a local leader who knew the community. And this wasn’t the first time he had been taken into confidence for an investigation. Ekramul thought this too would be another routine discussion where the police and intelligence needed his help.”

Forty-six-year-old Ekramul Haque was indeed a local leader from the ruling Awami League party. He’d grown through the party’s ranks, first as a student leader and then a leader of the Jubo League (the youth wing of the Awami League). At the time of his killing, he was a sitting city councilor in the city’s mayoral office.

“Honestly even the police had no idea this is how it would end,” the aide said. “What I’ve heard is the paramilitary were looking for a different person with the same first name. Ekram even told his captors that when taken into custody. But they thought he was lying. They’d come ready to kill.”

Although The Diplomat could not independently verify the claim, the hit list is said to have had the name Ekramul Hassan and not Ekramul Haque in it. But Haque’s captors passed this off as a clerical error and concluded he was simply lying to protect his skin. They went ahead with the execution anyway.

The meeting with the commissioner, however, can be corroborated from the tape.

In the first clip, Haque’s wife is clearly heard saying: “Please put me through to the commissioner – I’m his missus talking – hello… is the commissioner there?”

Haque is heard telling his little daughter to go to bed as his work at the police station will take him longer than expected.

“Honestly, the police had nothing to do with this,” the aide explained. “The paramilitary and intelligence people just took charge of him the moment he stepped in. The commissioner didn’t even have a chance to talk. They drove him off and the rest we all know.”

Not just the local police, but also Bangladesh’s nodal agency for narcotics control has distanced themselves from the killing of Haque.

Within hours of Haque’s family releasing the audio tape at a press conference and challenging the agencies to prove their claim that he was an armed and dangerous drug dealer, the Department of Narcotics Control issued a statement saying: “We did not have any file on Mr. Haque and we’re unaware of any record of his involvement in drug dealing.”

Even the general secretary of the Awami League, Obaidul Quader, grudgingly admitted that: “One or two mistakes can occur during the ongoing anti-narcotics drives.”

“Ekramul’s brother Ashraful worked with me in our campaigns against addiction,” Rashed Didarul, an anti-drug campaigner in Cox’s Bazar recounted. “At one point of time he was an addict, but later recovered under my care and the active support of Ekramul. He actually worked alongside me in the USAID backed de-addiction and anti-drug program. It is just absurd to claim that this family was involved in Yaba trade.”

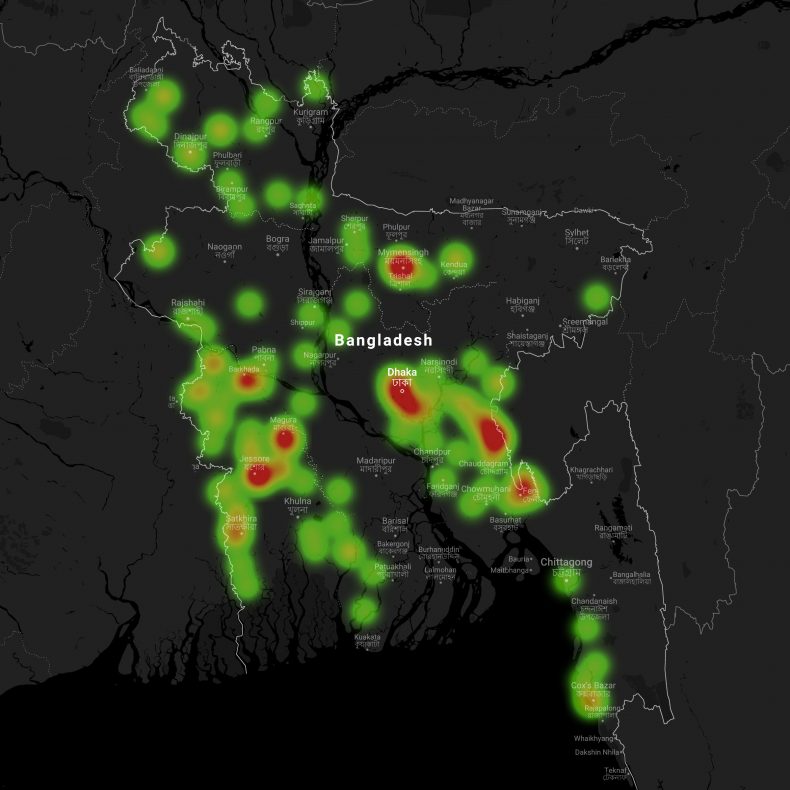

Heat map of the 157 verifiable “crossfire” killings in Bangladesh from April 1 to May 30, 2018.

The Crossfire Doctrine

In all of the 157 cases, the three agencies involved – the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), the Bangladesh Police, and the Detective Branch – claim the men were killed in crossfire.

In general, the standard line of explanation goes like this: The agencies conducted a raid, the agents were fired upon and the men who died did so due to retaliatory fire in self-defense. But the evidence to back this claim up has at best been thin if not outright dubious.

The authorities tried something similar in Haque’s case, but have thus far failed to convince many. There are multiple witnesses who saw him arrive voluntarily, unarmed. As for the tape, the RAB said they’re probing its authenticity – implying it was doctored to make them look bad and discredit the drug war. No follow up statements were issued.

“This is no war,” Nur Khan put it bluntly. “Let’s call it what it is – extrajudicial killings carried out in cold blood by government forces.”

Nur is a human rights activist who runs the Human Rights Support Society in Dhaka. He’s been documenting extrajudicial killings and providing legal and logistical support to those wrongfully targeted by the government.

In May 2014, Nur himself narrowly escaped abduction by the intelligence service, which view him as a troublemaker who was talking too much.

“Let’s assume for argument’s sake that these people who’ve been killed were drug dealers,” Nur continued. “Does that make it right to shoot them dead without due process and access to legal recourse? Is that the law of the land? And this claim of crossfire is patently bogus. Even the RAB claims to have found just country-made revolvers and a few Yaba pills on the bodies of these people. Let’s say the several witnesses who’ve seen these being planted on dead bodies were all lying. Even then… even then… tell me, who in their right mind, armed with a shabby country revolver engages in fire with a team of military personnel armed with assault rifles?”

Extrajudicial Killings as State Policy

Even though the Bangla drug war is being likened to what Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte has been doing in his country, the crossfire doctrine isn’t necessarily borrowed from him. Bangladesh’s present government has been using extrajudicial killings as state policy well before the recent drug war.

Ever since the Holey Artisan attack in July 2016, extrajudicial killings have virtually replaced regular investigative and police work. Brute force has gone from being the last resort in law enforcement to becoming the weapon of choice in all matters from fighting Islamists to quelling student protests.

Soon after taking office in 2009, the incumbent government enacted the Anti-Terrorism Act with a claim that it would be used to quell Islamist tendencies. Despite widespread international criticism, the act kept the definition of terrorist and terrorism vague and wide open. Bolstered by the successes of the War Crimes Tribunal, which sentenced to death past Islamists who had collaborated with the Pakistani army in 1971, the terror act was amended in 2012 and sweeping powers were given to the state and its paramilitary to execute and detain suspects without trial.

In 2016, bypassing the legislature, the prime minister’s office signed executive orders that gave paramilitaries and special units of the civilian police large, unaudited budgets and absolute autonomy of operations. These measures essentially allowed the agencies to operate with no fear of judicial or executive oversight — and to kill with impunity.

A host of human rights bodies like the Human Rights Watch, as well as foreign embassies, have raised concerns about the Bangladesh government’s trigger-happy ways. In March 2017, the UN Human Rights Committee expressly named the Rapid Action Battalion as being responsible for the extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances. The report says:

The Committee is concerned at the reported high rate of extrajudicial killings by police officers, soldiers and Rapid Action Battalion force members and at reports of enforced disappearances, as well as the excessive use of force by State actors. The Committee is also concerned that the lack of investigations and accountability of perpetrators leave families of victims without information and redress. It is further concerned that domestic law does not effectively criminalize enforced disappearances, and that the State party does not accept that enforced disappearances occur.

Political Fallout

In 2018, Bangladesh will hold general elections. The drug war has stirred in yet another violent complication in the already turbulent cauldron of Bangla politics.

“Yes, Yaba addiction is a huge problem in this country and is gnawing at the very future of our people,” A. Hassan, the general secretary of the student union of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party — the principal opposition party — said in an interview. “And no, there can be no tolerance to the spread of this. But the question is what does zero tolerance mean? How should that zero tolerance be put into practice? Do you just go shoot people dead or do you actually create a framework of laws and launch awareness programs to wean addicts away?”

According to many observers — including members of parties that are in alliance with the Awami League — the incumbent government has hit a massive low in popularity. The drug war is in part a desperate attempt to be seen as assertive, an attempt to win the voters over with decisive action.

“The crossfires in the name of fighting drugs are also a ruse to carry on with the political witch-hunt which this government has perfected,” Hassan continues. “The data is out there for everyone to see. Yaba boomed in this country after the Awami League took power in 2009. And it’s an open secret that their leaders are the kingpins of the trade. But have you seen a single major dealer being shot dead? [E]kramul Haque was an exception and he too was at best a mid-level leader of the League. All others killed have been just small fry — the mules who ferry Yaba for minimum wage.”

In May, a secret report from the Department of Narcotics Control was leaked to the press. It named Abdur Rahman Bodi — the Awami League’s member of parliament from Teknaf and longtime political strongman — along with his cousins and step-brothers as being the godfathers of the Yaba trade. The Bodi family were the main gatekeepers of the stock coming in from Myanmar, the report said.

In stark contrast with the alacrity with which the agencies have killed other people, the government dragged its feet in acting against Bodi or his family.

After trying to brazen it out for a few weeks and threatening journalists who had carried the news of the leaked report, in early June, Bodi fled to Saudi Arabia while his cousin and lieutenant Mong Mong Sen took shelter in Myanmar.

The reporting of this story was made possible with a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.