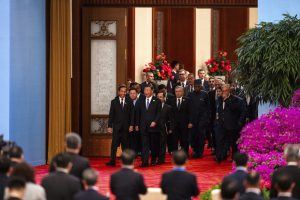

On October 18, top leaders from around the world gathered for a “family photo” at the third Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, China. The immediate takeaway was that it was a smaller grouping than previously seen.

The 2017 Belt and Road Forum counted 30 heads of state or government in attendance, including China’s own Xi Jinping. The 2019 edition expanded to 37 top leaders. This year, however, despite being the first Belt and Road Forum in four years and the big ten-year anniversary celebration to boot, just 23 heads of state or government attended (although there are more faces in the photo, including Nigeria’s vice president, the New Development Bank president, and the U.N. secretary general; see a full list here).

China tried to make the best of it, dragging its feet repeatedly on releasing the list of top level attendees and instead stressing the low-level representation. “[R]epresentatives from more than 130 countries as well as many international organizations” attended, China’s Foreign Ministry repeatedly emphasized.

While it’s certainly notable that the third BRF counted fewer heads of state or government in attendance than the first or second editions, there are a few mitigating factors. For one, the major crisis unfolding in the Middle East may have forced some leaders from the region to stay home. The UAE, for example, sent its prime minster to the 2019 BRF, but only a Supreme Council member to this year’s forum.

Another complicating factor is that a host of Asian leaders just visited China for the Asian Games. For many, it was simply too soon to turn around and make another trip to the country less than a month later. Kuwaiti Crown Prince Mishal Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, Nepali Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal, South Korean Prime Minister Han Duck-soo, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, and Timor-Leste’s Prime Minister Xanana Gusmao were among the foreign leaders to attend the opening of the Hangzhou Asian Games on September 23.

However, prioritizing the Asian Games over the BRF does send a message in itself. Sports are less politically controversial than the Belt and Road Initiative, so leaders could avoid some heat by visiting Hangzhou for the Games and using that as cover to skip the BRF.

But with those caveats in mind, there are some interesting trends to take note of. The most eye-catching is the lack of European leaders in attendance. The 2017 BRF counted 10 heads of state or government from European countries, accounting for one-third of all the participants. The headcount of European top leaders grew to 11 in 2019. This year, just three European leaders made the trip: Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic. Belarus, Czechia, Greece, Italy, and Switzerland all had sent top leaders to both the 2017 and 2019 summits, but skipped this year’s edition.

It’s a telling indication of how far China’s star has fallen in Europe, especially after Beijing’s tacit – and reportedly material – support for Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine. It’s also notable that Putin was one of the earliest confirmed attendees, likely as a result of Moscow’s need to demonstrate international support amid the pressure stemming from its ongoing invasion of Ukraine. Yet by making Putin’s presence a headline of the event, China may have pushed away any European partners who were on the fence about coming.

EU High Rep Josep Borrell did visit China from October 12 to 14 – pointedly not overlapping with the BRF.

It might be tempting to say that this year’s BRF reflects the way China’s diplomatic efforts have shifted toward to Global South. But that would be misleading. While China has indeed placed more emphasis on engaging with the Global South, we didn’t see a sharp spike in attendance from those countries. That’s the main reason for the drop in overall headcount: While Europe’s interest in the BRF dropped sharply, China wasn’t able to entice additional leaders from the developing world to attend.

One puzzling difference this time is the lack of top-level attendees from Southeast Asia. All 11 regional states – the 10 members of ASEAN, plus Timor-Leste – have signed Belt and Road cooperation documents. Seven Southeast Asian leaders attended the first BRF; nine attended the second BRF (and a 10th, Indonesia, sent its vice president). But this year, just half the ASEAN members sent heads of state or government: Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Of the Southeast Asian states who didn’t send top leaders this year, Malaysia, Myanmar, and the Philippines had attended the previous two forums. The reason for Myanmar’s absence is obvious: civil war plus a toxic reputation for the junta. The Philippines’ non-attendance is clear evidence of renewed tensions with China over the South China Sea; Malaysia’s non-attendance is more puzzling, but may also be tied to disputes in the South China Sea as well.

Meanwhile, just five top leaders from Africa – Egypt’s Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali, Kenya’s President William Ruto, Mozambique’s Prime Minister Adriano Maleiane, and Republic of Congo’s President Denis Sassou Nguesso – made the trip to Beijing for the forum. That ties the headcount from 2019, although Egypt and Mozambique both sent their prime minsters, rather than the more powerful presidents.

There’s a curious gap between the number of African states that have signed on to the BRI – 57, with eSwatini and Mauritius the lone exceptions – and the number of states sending leaders to the Belt and Road Forums.

A similar gap exists for the Middle East, where every country except for Israel and Jordan has signed on to the BRI. Yet only the UAE has ever sent a top leader to a Belt and Road Forum (once, in 2019). The UAE downgraded its representation this year amid the turmoil in Israel.

And no state from Central America and the Caribbean region has ever sent a head of state or government to a Belt and Road Forum, even though 13 states from the region are part of the initiative.

This could signal one of two things, or possibly both: Either signing up for the BRI doesn’t really tell us much about a government’s foreign policy priorities, or BRI members don’t see the Belt and Road Forum as a big deal. Amid concurrent global crises in Ukraine and Israel and pressing economic issues for many countries at home, even most BRI leaders choose to RSVP “no” to the big 10th anniversary celebration in Beijing.