Since April 1997, when Russian President Boris Yeltsin and China’s leader Jiang Zemin first announced their intention “to promote the multipolarization of the world and the establishment of the new international order,” academics and policymakers alike have both fretted over their strengthening ties and debated whether the China-Russia partnership would eventually materialize into a political-military alliance pointed at the United States and Europe.

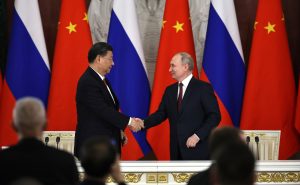

Today is no different. The “no limits” joint statement, signed by Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping just weeks before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and China’s subsequent transfer of critical dual-use technologies and intermediary role in circumventing Western sanctions, has resurfaced such debates.

While ties have certainly gotten closer since the 1990s, recent indicators may point to strains in the Sino-Russian relationship. From around the time of Putin’s last visit to Beijing in May 2024 to mark the 75th anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and Russia, Chinese leaders have substantially shifted China’s official rhetoric regarding Russia. The 2024 meeting’s bilateral statement, in sharp contrast to the 2022 statement, lacked mention of “no limits” or “no forbidden areas of cooperation,” and instead emphasized the China-Russia relationship being defined by China’s traditional foreign policy principles of “non-alignment, non-confrontation and non-targeting of third parties.”

Similar shifts seem to be occurring in the personal relationship between Xi and Putin. If Putin described their relationship “as close as brothers” in May 2024, Xi opted for a more subdued “a good friend and a good neighbor.” This is starkly different from Xi’s categorization of Putin as his “best, most intimate friend” in June 2018.

Similar changes are occurring in public discourse. Not only are Chinese scholars today able to discuss Beijing’s allegiance to Moscow in the open, but they also criticize it. In 2022, the Chinese government censored Chinese historians who were denouncing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and calling on Beijing to take a firmer stance, but in 2024, Feng Yujun, a professor at Peking University, was allowed to publish an article in The Economist, outlining four factors that make Russia’s eventual defeat inevitable. Shen Dingli, a leading scholar of Chinese security strategy at Shanghai’s Fudan University, echoed Feng’s sentiment in the Chinese national press and stated that China doesn’t want the world to view it as collaborating with Russia against Ukraine. He further pointed out that “China’s change of expression is a rational assessment of the impact of the Russia-Ukraine war.”

These statements are important as they provide insights into Beijing’s strategic mindset. After all, leading Chinese scholars often act as government agents, explaining and justifying the government’s opinions. For instance, months leading up to China’s announcement of an economic stimulus plan in September 2024, Chinese economists published articles detailing how consumption needed to grow vis-à-vis investment. The fact that these Chinese scholars, acutely aware of the political environment they work in, criticized Putin’s Russia directly and publicly implies either that they felt there was an opening to provide such feedback, or that the government already had a plan along similar lines in the making.

China’s cautious approach toward Russia is also visible in other sectors, particularly finance and energy. Following U.S. threats of secondary sanctions, Chinese banks began halting transactions with Russia. While trade in commodities like oil and grain remains largely unchanged, such Chinese actions resulted in the freezing of tens of billions of yuan in payments and increased transaction costs (from close to 0 to 6 percent) for Russian firms using intermediaries. Moreover, in the second quarter of 2024, due to payment difficulties, the Bank of China decreased its assets in Russia by 37 percent, and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China reduced theirs by 27 percent.

Regarding energy, despite Putin’s continuous push for the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline and broader energy cooperation with China – evident in over 12 communiques since February 2022 and, most recently, Xi’s trip to Russia in October 2024 – no concrete progress has been made. Beijing has continued to stall progress over pricing demands, requiring further concessions from Russia, most likely in the form of discounts. This highlights Beijing’s self-interested and realist approach toward its cooperation with Russia. Xi is certainly not doing Moscow any favors by buying Russian gas at a 40 percent discount. Given that the United States has been China’s sixth largest source of liquefied natural gas imports between 2016 and 2023, a signed Power of Siberia 2 deal would mean reduced import of U.S. gas. That’s a card China wants to play carefully, especially as the United States welcomed a new president in January 2025.

A straining Sino-Russian relationship offers the West an opportunity. Instead of imposing further tariffs on China, U.S. President Donald Trump should not alienate China, at least not before Russia and Ukraine negotiate an end to the war. China substantially benefits from the existing liberal international order with little to no intention of destroying it. Its recent actions toward Russia indicate that China cares about its relations with the United States and Europe, specifically its economic interests. Trump imposing more tariffs against China may not only encourage China to shift more firmly toward Russia, but it could also undermine the Western efforts to support Ukraine’s fight for freedom. Stronger Sino-Russian cooperation, especially in the military domain, is dangerous.